If I seemed to get overly excited a few days ago after finding evidence that Thomas Lovewell’s eldest daughter really did call herself “Julanay,” consider how long I’ve been looking into the matter. My search began almost exactly twenty years ago. On the last day of 1998 I stood shivering in White Rock Cemetery, pondering the inscription on a tombstone that suddenly threw a wrench into the traditional timeline of Thomas Lovewell’s life story. Here was evidence that the man who was supposed to have disappeared into the mists of the Rocky Mountains in 1849, not to reappear until 1865, had fathered a child in Kansas around 1856.

What I’ve learned since then certainly hasn’t diminished the Kansas pioneer’s legend, but it has reordered events and put them in their proper historical context. It seems that Thomas didn’t join the California Gold Rush in 1849 as we had long been told, but instead became part of the mad dash to Denver in 1859. He wasn’t rattling around aimlessly in the Far West for sixteen years, but spent only six years there, three of them serving in the Third California Infantry. He did not, as the story went, return home to find his wife dead and his family scattered. Unless you’re new to the site, you’re probably well-versed on how that situation turned out.

We’ve learned what became of many members of the supporting cast in Thomas Lovewell’s story, including the wife and child he left behind in Iowa in 1859. However, while new information has revealed some of the contours of their lives, there was a sudden reversal of fortunes in the early 1880’s that has remained a mystery until very recently. Thanks to the availability of many more local newspapers from the era, it now seems that the Turnbull and McCaul families went into a steep decline because Kansas decided to sober up.

After watching her daughter Julanay wed an enterprising Irish lad named Edward McCaul in 1871, Nancy Lovewell decided to remarry the following year, probably after serving a get-acquainted stint as maid for widower Michael Turnbull and nursemaid for the four youngest of Michael’s five children living on a farm near Gallatin, Missouri.

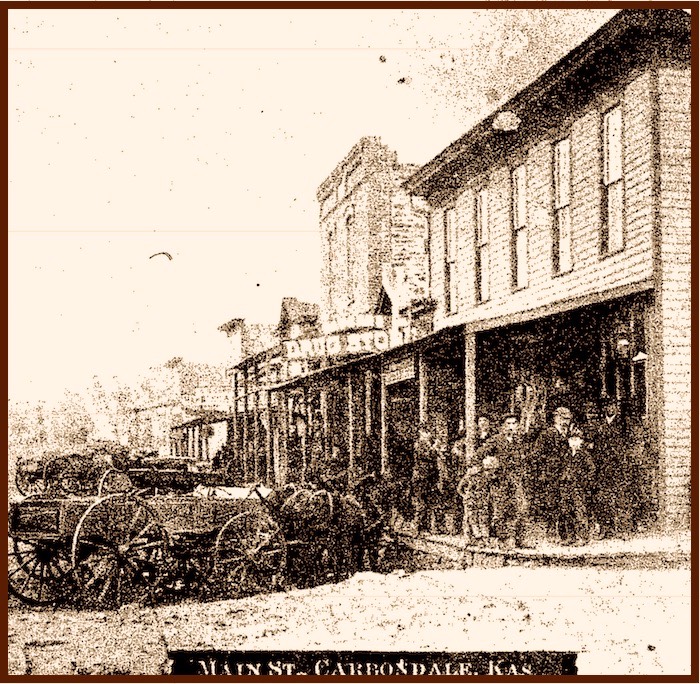

By 1874 the Turnbulls had moved to Carbondale, Kansas, south of Topeka where Michael labored in the coal mines that gave the town its name. When the 49-year-old known as “Uncle Mike” broke his leg that year, neighbors chipped in to furnish a lunch wagon so he could provide for his family by selling baked goods and sandwiches to passersby while he was hobbled. After his leg healed Michael did not return to the mines, but apparently leased a little shop on Carbondale’s Main Street where he continued to sell cakes and candy and other treats. It was probably just after his new wife’s daughter and her young husband moved to town that Michael Turnbull's prospects improved substantially.

In 1877 Edward and Julanay McCaul established themselves in Carbondale with some fanfare. Edward and his wife bought five prime lots in a new addition in the southwest part of town and purchased a pair of adjoining commercial buildings on Main, halfway between the opera house and the hotel, where they opened a restaurant and billiards parlor. Space in one of these buildings was also leased out at various times as a knick-knack shop, a shooting gallery, and an auction house. A corner of one of the McCaul buildings also may have served as a new home for Michael Turnbull’s business, which practically advertised itself as being a bit shady.

Mr. Turnbull has moved his confectionary and bakery into his new building where he has a private room where the weary may rest and refresh themselves. “Uncle Mike” is a jolly old fellow and worthy of patronage.

-Osage County Chronicle 15 Mar 1877

In 1879 Turnbull proudly proclaimed that he was on Main Street to stay, installing a new sign over his bakery which the local paper called "a 'Boss' job." The sign arrived just in time to direct traffic to buy "Fire-crackers for the 4th at Uncle Mike Turnbull’s. Come and see 'Uncle Mike Turnbull' on the 4th of July he will dish you up anything you want."

One year later the 1880 census found the extended family still looking prosperous and hopeful. Michael Turnbull and his wife Nancy, who went by her middle name while in Kansas, either “Maria" or “Mariah," were raising Nancy’s youngest daughter Alice. Cora Alice Turnbull was enrolled in school and learning to read and write, something neither Michael’s new wife nor his eldest daughter Susie could do. Still living at home at the moment, Susie had recently married a railroad engineer named John Robinson and would soon join him in North Platte, Nebraska. Nancy’s daughter and her son-in-law, the McCauls, lived a block south of Main on a spacious corner dotted with fruit trees. There, Julia looked after her two boys, three-year-old Eddie and baby Willie.

Judging from the picture painted by the 1885 Kansas census, sometime between the two enumerations a wrecking ball had collided with the family and dashed their dreams.

By 1885 the McCauls and Turnbulls of Carbondale lived in a single dwelling, the Turnbull house, the McCaul residence with its orchard and fenced yard having been sold for $250 cash some two years previously. Michael Turnbull, no longer “Uncle Mike” the baker, had become a laborer digging wells for a living. Susie Turnbull had moved back in with her parents and declared herself to be a single woman once more, though her former husband John Robinson was also back from Nebraska and living in the very same house, when he was not risking his life in the Carbondale mines to put some food on the table. Missing from the picture entirely was Edward McCaul, off someplace else with his eldest boy Eddie, Jr. Julia McCaul was still looking after Willie, along with the two newest additions to the McCaul family, Freddie and Alice, as well as two little Robinson girls who had been born in Nebraska to John and Susie.

We may never know what led to the rift between Julanay and Edward McCaul in Washington Territory, or what poisoned the Robinson marriage on the Plains of Nebraska. On the other hand, it has become quite clear that the single event that changed the fortunes of the Turnbulls and drove the McCauls out of Carbondale in the first place was the arrival of prohibition.

A constitutional amendment abolishing the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages in Kansas took effect January 1, 1881. A number of saloons in Carbondale closed for a time that year and then reopened when no one was looking. Though the law was more stringently enforced by 1882, some saloon men kept at their vocation by paying the $100 fine every month, considering it a cost of doing business. Soon, frustrated authorities began arresting drunks, and then the proprietors who fueled their binges. While juries seldom returned a guilty verdict, fines and mounting legal bills forced the saloon keepers of Osage County to close up shop. Edward McCaul put his house on the market in February 1883, slipped out of town, and was reportedly scouting for new prospects in San Francisco early the following year.

Julanay McCaul remained in Carbondale long enough to cash in her markers from local businessmen and sell the couple’s buildings on Main Street before boarding a train with her children to join Edward in Washington Territory in May of 1884. We can only guess about the reason for her return to Carbondale a year later without her husband or her firstborn, a homecoming which drew her into the orbit of the forlorn Mr. Robinson. What we do know for sure is that she and John Robinson would head west together in time for their daughter Lillie to be born at Portland at the end of January 1887.

Mr. and Mrs. Turnbull and daughter Susie migrated a few miles north to Topeka, where Michael may have hoped that his back-alley liquor sales would escape detection in the bustling city. He tried to start over in Topeka as he had done in Carbondale, selling snacks on the street from a lunch wagon, but his request for a waiver of the license fee was denied by the city commission. In 1889, one year after his wife died of a bowel ailment (possibly a case of typhus) he was arrested for bootlegging, fined $100 and later imprisoned to make him work off his debt. The State of Kansas may not have gotten its money’s worth out of Michael Turnbull, who, as his 70th birthday approached, was released to the city poor house, the last place we hear of him.

Nearly twenty years after achieving statehood, Kansas had fired its first salvo in what was to be a continuing war on alcohol. As with any war, there was some collateral damage.

Picture of Carbondale from a 1972 City Centennial Booklet