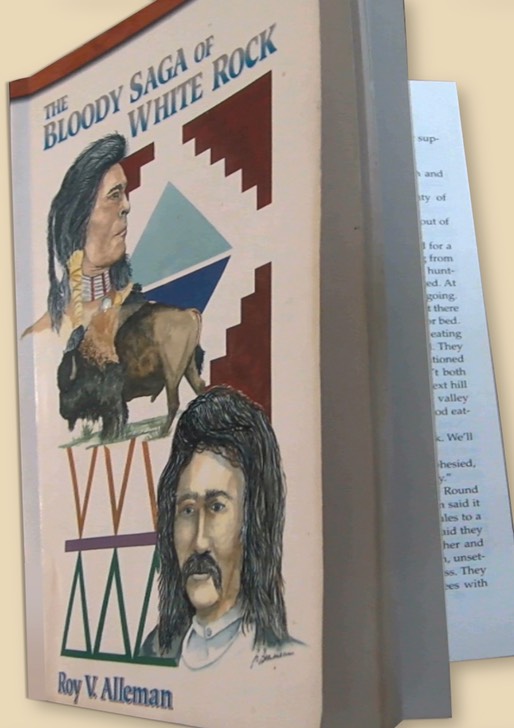

A few friends have reported that they’ve begun reading The Bloody Saga of White Rock. While encouraging, the news also fuels some trepidation. Thumbing through Roy Alleman’s book over twenty-five years ago is what set me on a path of discovery, but it also led me down a few wrong turns right off the bat.

While reading it, remain aware that the book is fiction "based on a true story," but still fiction.

More than once I’ve mused about digging out my old copy and marking it with corrections. The task would be more time-consuming than it sounds.

Reading the opening paragraphs recently, reminded me of what a fine, descriptive writer Alleman was. His prose style makes the book a seamless companion-piece with George W. Schiller’s The Abolitionist,* the story of Albert Gallatin Barrett, who settled in the valley of the Black Vermillion in Marshall County, Kansas, two years before Thomas and Nancy Lovewell joined the abolitionist Ohio Town Company in 1856.

Their arrival in Kansas that year points to the chief fault of Alleman’s book as a history text, which is that its timetable is not only unreliable, but completely out of whack most of the way through.

Thomas never claimed to be a forty-niner, and by sending him to California in 1849, the author eliminates any notion of all the things he was actually doing instead: his time as a pioneer land speculator in Iowa during the Crimean War, or as one of John Brown’s followers in Territorial Kansas, hauling mail in Marshall County, and scouting for the Army. The daughter whom Thomas famously left behind when he finally did head for California, was not even born until 1857.

After installing Nancy and their daughter Julany on a farm near Nancy’s brother in Iowa, Thomas finally did leave for Pikes Peak in early spring of 1859, stopping there only briefly before moving on to California to meet up with his brothers Solomon and Alfred that November.

Death Valley Days

A few of the anecdotes provided to flesh out Thomas’s time in the Far West (which amounted to only six years, not sixteen) may have been tales he heard others recite, not adventures which he had experienced first-hand. The harrowing ordeal in Death Valley described by Alleman, may be one of these.

In 1849 thirty-eight young men from Illinois who lived within a few miles of the Lovewells, set out for California together. Receiving a bogus map that promised a shortcut to the gold fields, they wandered around lost in the hellish landscape of Death Valley for weeks before discovering water just as the whole company seemed about to die of thirst. In the end three men perished and the survivors found no gold to speak of, but apparently did anoint the mysterious valley with the name we know today.

"Spring, 1865"

After Thomas returned from prospecting and military service in California, the Lovewell and Davis wagons did not roll into the valley of the White Rock until the spring of 1866. Alleman not only adheres to an erroneous timetable proposed for Thomas, but even brings Custer to Kansas a year too early so he can drop by the Lovewell cabin and discuss the dangerous situation simmering on the Plains.

It seems unlikely that Thomas Lovewell ever had a heart-to-heart chat with George Armstrong Custer about Indians, although it is possible that he knew Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok, who also scouted for the Army around the same time.

“Orel Jane and Tom exchanged vows…”

The complicated marital history of both Thomas and Orel Jane is tidied up for the book with an invented death for Nancy Lovewell (who was Orel Jane’s aunt, not her sister) during Thomas’s absence, and Orel Jane’s swift marriage to and divorce from Alfred W. Moore, who supposedly died in the Civil War shortly after the ink was dry on their divorce decree.

In real life, the War was over before Alfred W. Moore decided that it was also time for the marriage to be over, handing Orel Jane enough money for a train ticket to her parents’ home near Osceola, Iowa. When she crossed the threshold of the Vinson and Julana Davis residence with her infant son in her arms, she may have been surprised to find Thomas Lovewell bunking under their roof.

"Emery Perry Moore"

Soon after arriving in Republic County the following year, Orel Jane entrusted little Vinson Perry Moore to her parents’ neighbors, Sylvester and Diantha Haynes of Clifton. The boy would take turns living with the Haynes family or with his grandparents, but would have little contact with his mother ever again. The first name “Emery” was what the young later decided to call himself.

In 1879 Alfred Moore, then an itinerant plasterer, would visit his former wife at White Rock and drop in on his boy at Clifton. Rebuffed by both, he would move on and disappear from history.

After remarrying in 1872, Thomas’s first wife Nancy also stubbornly clung to life until 1888, when she died at Topeka. The Lovewells of Jewell County were duly informed of her passing by a letter from another of Orel Jane’s aunts.

Most of Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell’s children were aware of Nancy’s death and surely would have learned more details about their parents’ past when their half-sister Julany arrived in Jewell County five years later with several children in tow. Thomas celebrated this reunion by getting a shave and haircut and having his portrait made at a photographic studio in Courtland with his long-lost daughter at his side.

The portrait became the most familiar image of Thomas Lovewell, reproduced in newspapers accompanying news of his 89th birthday, his death four years later, Ellen Morlan Warren’s tales of the settlement of White Rock, and the banner at the top of this page.

(To be continued)