There are so many anniversaries to celebrate right now. The TV station where I worked for 47 years just turned 70. This website has been around for one decade. And it was almost exactly 25 years ago that I decided to investigate Lovewell history.

My son and I headed to Formoso for a New Year’s visit at my mother’s house. My wife or daughter must have been ailing just then and weren’t feeling up to a 500-mile drive on a cold winter’s day. Jonathan and I listened to one of my Christmas gifts, an audio cassette of Steve Martin’s latest book.

I asked him a few months ago if he could remember the chapter that made me pull of the road in Manhattan. Of course he remembered. It was a bit about warning labels that had me laughing so hard I no longer had complete control over the car and had to pull over. Thanks, Steve.

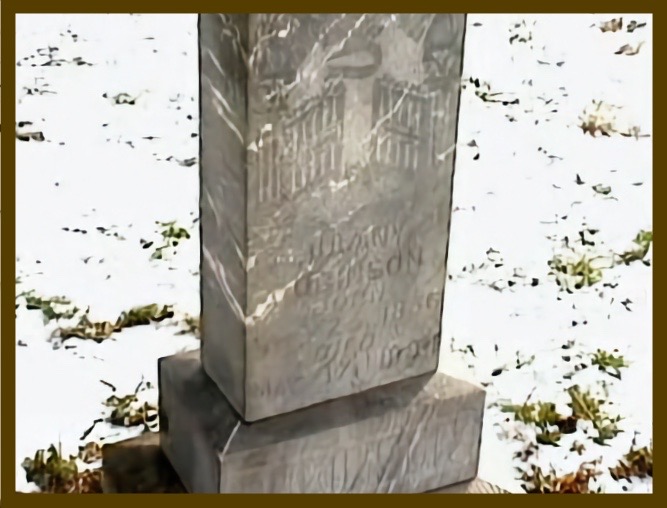

There was one side-trip on my agenda for that visit. I had told my mother that I needed to visit the cemetery where her grandmother was buried: White Rock Cemetery.

Her grandmother was Julany (Lovewell) Robinson, a daughter Thomas Lovewell had left behind when he followed the trail of the 49’ers to California, according to The Bloody Saga of White Rock, Nebraska author Roy Alleman’s account of the life of the legendary Kansas pioneer.

My brother Charles drove my mother’s old Taurus over pebbly washboard roads on the coldest day of that winter. Charles was getting around on crutches just then because of a nagging pain in his hip that would eventually drive him to see a doctor. It was a bright morning with a thin cloud cover, zero according to the thermometer, with a light but punishing breeze. I’m reminded of the wind-chill factor as I watch video of my son attempting to find a position which will keep the legs of his pants from coming into contact with his flesh.

We did not stay long after finding my great-grandmother’s headstone, but it was long enough to note the years of Julany’s birth and death which set the gears running in my head. How could Thomas Lovewell have fathered a child in 1856 if he set out for California from Illinois in 1849 and didn’t return until 1865?

An obvious answer might be that she wasn’t his child. Yet, he would rush to St. Louis to scoop up the young woman and her children, give her a house in Lovewell, and have a portrait taken with her at his side.

Something about the standard model of Thomas Lovewell’s life and career was definitely out of joint.

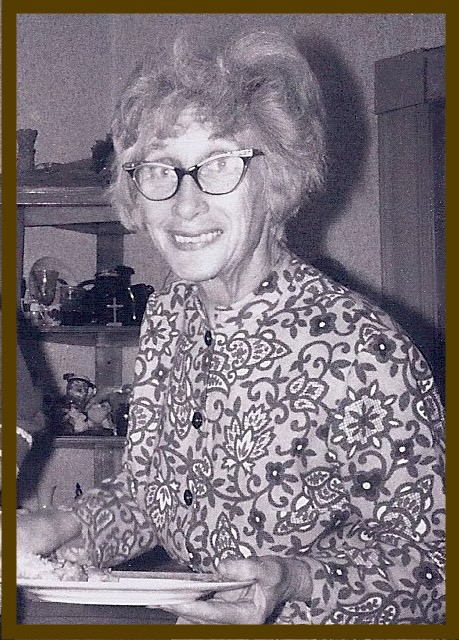

In the video I shot that day before we were quickly driven away by the bitter chill, my mother mutters something about consulting Aunt Ruth, “She knows all that stuff.” If Ruth knew, she would take the answer with her to the grave that year, a few weeks before Charles died from prostate sarcoma.

Ruth had been the keeper of family knowledge and the first person ever to show me a yellowed newspaper clipping that bore a photograph of Thomas Lovewell. There is no photo of Ruth in which she does not look bright-eyed and inquisitive, with a head full of interesting facts which sometimes spilled out into notebooks adorned with pictures clipped from newspapers and magazines.

Ruth died at 88 shortly before the world’s odometer turned over to a new century full of gadgets and innovations and dotcoms.

It’s a shame she did not have a few more years to enjoy. Ruth would have loved posting on Facebook.