When Thomas Lovewell arrived at Shasta, California at the end of 1859, how did he get to Sacramento to meet up with his brothers Alfred and Solomon? Probably by coach. It was a jostling ride of 36 uncomfortable hours with a sleepover at Marysville. We know this and a few hundred other details about how things worked in the 1850’s because one man who made the trip wrote down not only everything he did, but how he felt about it.

In The Lost Gold Rush Journals, as we watch Daniel Jenks trudge past a familiar diorama of the American West, we can hear a vibrant interior monologue as he narrates the journey in his head. Alone at night in his cabin, Jenks jotted down his thoughts on the day’s activities, later transcribing this diary into a journal which, besides holding a place of honor in the Library of Congress, forms the core of Larry Obermesik’s 2021 book.

Reading it reminded me of something that I couldn’t quite put a finger on until I revisited the chapter concerning the traveler’s second visit to San Francisco.

Sauntered around this phoenix-like city today, in search of novelties and truly I found a plenty. No other city in the world I will venture to say presents just such a variety of nations as this. Here are streets of Chinese stores, warehouses and dwellings where a man might well imagine himself in Canton or Shanghai, judging from appearances.

In other places are German lager beer saloons, all after the old fatherland style and here are the Mexican fandangos, the French cafés, the English Porter shops etc. All nations and tongues are here.

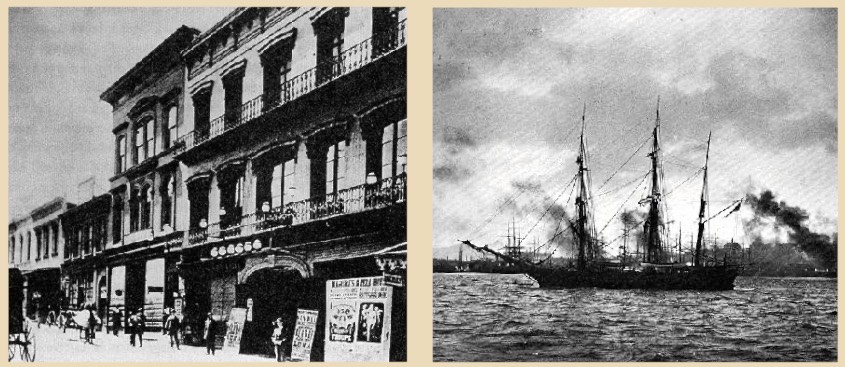

To help set the scene, I happened to find a website with pictures of early-day San Francisco within a year of Jenks’s visit, including the opera house which he talks about next. Although he got the name wrong, he came close enough that we know what he meant.

Tonight, went to see the Negro Opera at McGuries. The singing suited me very well, but I suppose I am no judge of music and therefore I’ll not say any more about that.

Yes, that’s the moment when the comparison hit me. The whole time he was in the West, Daniel Jenks reminded me just a bit of Forrest Gump.

He took part in both historic migrations across 19th Century America in search of gold, traveling by ship, train, steamboat, and ox-cart, usually without a firm plan. During his wanderings through the interior of the continent he crossed paths with Mexican bandits, white marauders, hungry wolves, greedy Mormons and vengeful Indians, always narrowly escaping dire consequences.

He nearly starved to death, survived for weeks on nauseatingly contaminated water, and endured a series of polar nights without wood for a fire. And yet he never felt better in his life than when he was on the trail to his next destination. When he finally decided to return home to Rhode Island for good, he lasted only four years, cashing in his chips at the age of 41. He was outlived by both of his parents.

I had to check the index to see if he ever compared life to a box of chocolates. Sadly, he did not, although the subject of chocolate did come up when he recounted “partaking of a regular Mexican dinner of chili, colarow, frijoles, tortillas and chocolate.”

By the way, while Maguire’s Opera House sometimes did play host to an Italian opera company, I strongly suspect that what Jenks actually witnessed on July 17, 1857, may have been a minstrel show - but the jury is still out.

At the start of his journal Daniel Jenks offers a piece of homespun philosophy, part Shakespeare, part meeting-house benediction:

This life is but a dream, at best. May we all meet at the grand awakening after death.

And that’s all I’ve got to say about that.

https://books.apple.com/us/book/the-lost-gold-rush-journals/id1575520931

The Lost Gold Rush Journals by Larry Obermesik