Most of the cockeyed genealogy embedded in Gloria Lovewell’s 1979 book “The Lovewell Family” owes its genesis to Sherman Lee Pompey’s 1962 “The Wolf and Little Wolf,” a scholarly tome which traces the Lovewells of America back to a family of Lovells who arrived from England around 1635. It’s a wrong-headed notion and I’m not sure Gloria entirely bought into the idea, since she throws in a page or two of misdirection at a crucial moment in the story, covering the presto-chango transformation of one family name into another, with a literary puff of smoke.

Both books are rather long and stuffed full of dates and ages, a few of which are bound to be wrong. However, some of “The Lovewell Family’s" most glaring and puzzling errors, such as placing Thomas Lovewell’s death three weeks too early, also turn out to be copies of mistakes made by Sherman Lee Pompey, who was a brilliant family sleuth but a shabby proofreader.

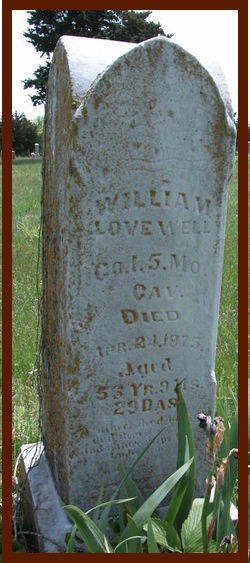

I’ve lazily passed along some of those mistakes myself, such as accepting the year of William Lovewell’s birth as 1822, because Pompey carelessly transcribed the inscription on a headstone in a country cemetery between Pleasanton and Trading Post in Linn County, Kansas. The stone, shown at the right, records the date of William Lovewell’s death, and then gives the length of his life in years, months, and days, letting interested family researchers do the math for themselves. Unfortunately, Pompey dropped the part about the “9 Ms.” shoving William’s birth into a different calendar year.

For the record, Thomas Lovewell died March 23, 1920, William Lovewell was born in 1821, and there’s no evidence that the Lovells and Lovewells were even aware of each other. John Lovell and John Lovewell embarked from different English ports, arrived in America at different times, lived in different parts of Massachusetts, and served in different companies during King Philip’s War.

Even if Sherman Lee Pompey himself wasn’t quite convinced by the feeble straw he had grasped to connect the Lovells with the Lovewells, hitching the two families together solved a logistical problem for him. He had reams of historical data tracing the ancestry of the Lovells, but there was hardly enough about the Lovewells to pad out a booklet of their own.

What the latter family did have was a wealth of gripping, gritty tales of survival along the American frontier. Most of these were written by Lovewell historian Orel Elizabeth Poole, concerning her grandfather, Thomas Lovewell. However, the descendants of Thomas’s brother William, a family which Pompey married into, preserved their own collection of family anecdotes. One of these stories, recorded by William Lovewell's granddaughter, Mary Roberts Nelson, involved a mysterious incident in the life of William’s daughter Mary, a daughter who never married.

In our little town in Kansas was a little house where the spinster sister Mary lived. Occasionally she would visit my mother in our home, and once in a while mother’s two sisters, Amanda Boyd and Emma Medley and brother William Wallace Lovewell.

When I was about eight, she was brought to our house badly beaten and a bloody mess. My mother, being close in both kin and relation, was where the town officials brought her. I remember my mother weeping and washing her long black hair free from blood clots and administering medical aid to her bruised up condition. She remained with us some time to recover.

One day Uncle Wallace came with two other ladies, both very dignified and clothed in good taste, and both kissed my mother and cried a little. Then the four of them talked with this injured sister. After a time they dressed her. She was a very aristocratic lady. They packed her baggage and my uncle then took her to the railroad station. I learned by listening to this and mother’s conversation that they were taking her to Lawrence to live dividedly between her own two sisters. I never heard any more about any of them, ever.

Today we’re able to fill in some blanks in the story with the help of resources Mr. Pompey couldn’t have dreamed of in 1962 - online newspaper archives and burial records. From them we may deduce that Mary Lovewell was not going off to live with her sisters, at least for any length of time.

The first public sign that Mary Lovewell needed special help may have come in 1904 when she was charged with disturbing the peace of the Thirlwell family of Pleasanton, Kansas, while evidently acting in a deranged manner. After hearing testimony from sixteen witnesses, a jury at Mound City judged her to be sane but guilty of the misdemeanor, and fined her one dollar. Less than four years later came the beating that changed the course of her remaining days, reported by the Pleasanton Observer on January 9, 1908.

WAS IT ROBBERY?

Mary Lovewell Found Almost Dead In Her Home Saturday.

Mary Lovewell, a half demented woman who lives all alone just north of the stock yards, was found in her home last Saturday evening in an unconscious condition with bad bruises about the head and face. From the indications she had been in that condition about 24 hours. She was at once moved to the home of her sister, Mrs. Zack Roberts where she has been ever since. She has been gradually recovering but is still very weak.

She is supposed to have had about $115 in the house and so far none of it has been found. She has revived enough to tell of two men coming into the house and that is all she can remember. There is quite a mystery connected with the affair and so far there has been no clue to the guilty parties.

Mary may have caused another public commotion after recovering from the beating, because a hearing was conducted at La Cygne in April, perhaps a few days before William Wallace Lovewell held that family council with his sisters. This time Mary was “adjudged insane and matter certified to Board of Control.”

Although she may have lived with her sisters on occasion, she died in 1913 at the Osawatomie State Hospital and was buried in a cemetery north of town.

William Lovewell had two daughters named Mary, both of whom Sherman Lee Pompey identifies as spinsters. Gloria G. Lovewell notes that the second girl did wed an unnamed man, but had no children. The first Mary was born to William’s second wife, Martha Morris Ogden, the later one to William’s third wife, Matilda Wise. According to her burial information, the woman in the hospital plot, a daughter of William and Martha Lovewell, was born in 1852.

A note on Findagrave.com gives the following information about the place:

The Osawatomie State Hospital Burial Grounds are located north of the city of Osawatomie, Kansas. It is a small cemetery consisting of 346 markers identifying people, mostly patients, who had no families that would claim them. Burials were discontinued during the early 1950's.

Interments are identified by large numerals inscribed on the headstones.