My most recent blog post, “A Wonder at Pikes Peak,” illustrates how it’s possible to run on for 1,300 or so words about a minor topic (exceeding a limit imposed for the sake of brevity), while leaving so much unsaid. For instance, I neglected to include a link to the Pikes Peak picture itself, since I was treading over already thoroughly-trampled ground, with numerous examples of the photo scattered around this website. However, anyone stumbling upon the essay because it contains a reference to Wonder Woman, might be left scratching his or her head, before quickly moving on. Brevity might be the soul of wit, but in my hands it can often be a source of confusion.

Another matter I wanted to touch on was serendipity, as I excitedly informed my wife over lunch at the local deli. I explained how I had recently started looking into an obsolete photographic process to learn exactly how the Pikes Peak photo might have been ruined, only to find references to the method popping up everywhere, including the movie we had just watched, in which a band of heroes have their portrait made in a little French village in 1918.

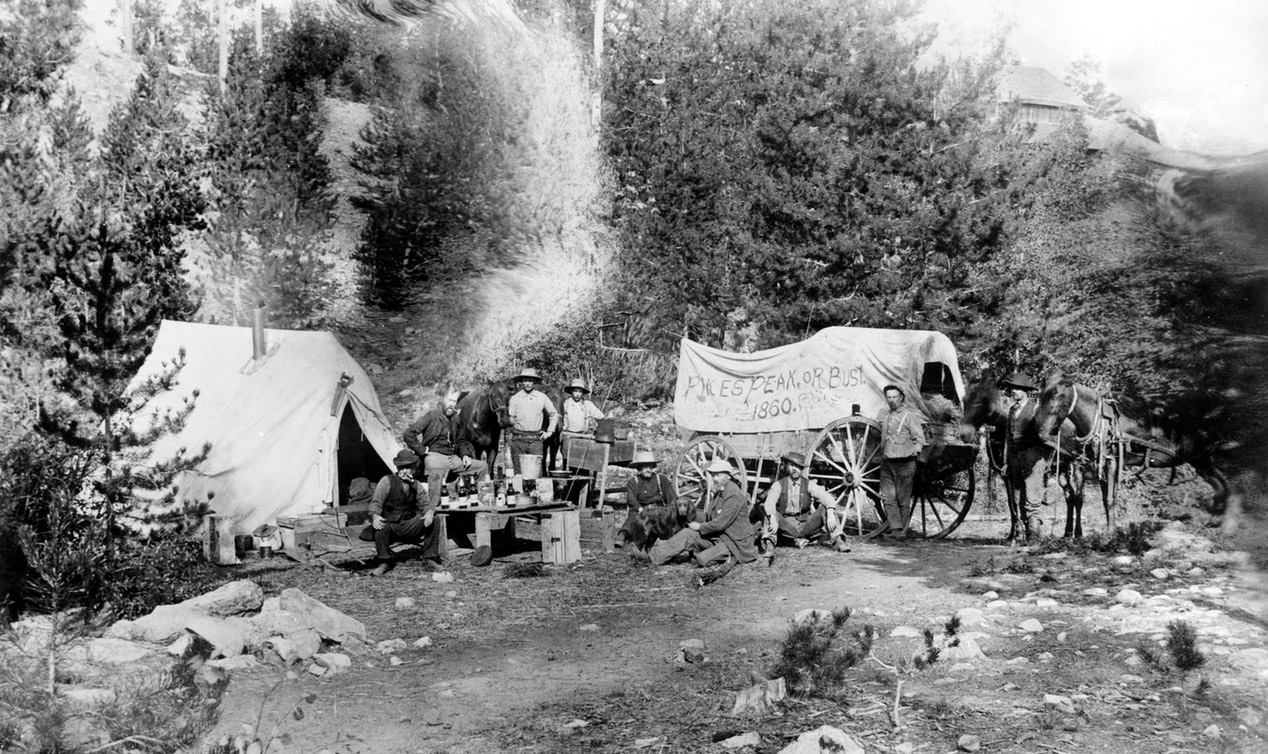

“Belgian,” she corrected. “They’re not in France. They’re in Belgium. It’s a Belgian village.” I made a mental note to tweak a geographical reference in my post, as well as to include a link to, or another version of, that 1859 photo taken at Pikes Peak. Noting that most of my previous postings are scaled down or involve some degree of cropping, here is the original file in all its ruined splendor (click on the picture to enlarge in a new window).

Before 1855, the pinnacle of photographic art in America was the daguerreotype, an innovation imported from France by Samuel F. B. Morse, who, besides being an inventor himself was a painter of some renown, and also taught classes in painting and photography in New York City. One of Morse’s students was Mathew Brady, a young man whose name would become synonymous with Civil War photography.

Daguerreotypes were made on polished copper plates which were coated with silver and bathed in iodine vapor before being loaded into a camera. After exposure, the plate was developed in a cloud of mercury vapor and then washed of any unexposed silver iodine, leaving a positive image on the plate. No one seemed to complain that the result was a single mirror-image photograph that could only be copied by having another deguerreotype made of it.

Mathew Brady was already a master of the daguerreotype by 1855, when he invited an Englishman named Alexander Gardener to show America his latests improvements to a new wet-plate collodion process. Collodion, Brady soon learned, was a sticky, photo-sensitive syrup, which was poured over an ordinary glass plate inside a darkroom. After any excess collodion was drained off, the plate could be loaded into a light-tight frame, ready to be inserted into to the back of a camera.

Ideally, the glass plate had been evenly coated with a thin, gooey layer of collodion. To understand how the Pikes Peak photo may have become damaged, remember that the image in a camera is formed upside-down. An extra little blob of syrup may have congealed eactly where the forehead of D. C. Oakes would soon appear. The blob may have begun to ooze south by the time it was inserted into a camera, well before being bathed in developer, washed, dried, and then treated with a coat of shellac, which contains alcohol, and may have contributed to the damage.

I’ve hinted before that the main reason we have this picture is because, having no use for it, Oakes apparently gave it to John H. Williams, the man in the big white hat. Although Williams went home to Michigan, later moving to San Jose, both his son and grandson became well-known lawmen in Gilpin County, Colorado. Late in life, John Williams’ grandson would donate the photograph to the Denver Public Library, without providing any information as to who or what it depicted.

It’s hard to support my suggestion that we wouldn’t know of the picture if it hadn’t been ruined. Oakes probably planned to send a copy wherever he shipped a crate of his guidebooks, and since he evidently enjoyed having his picture taken he would have kept one for himself. In fact, he might have kept a great big one. Besides being easily copied, another advantage of the collodion negative is that it could be enlarged. It might have become a poster of the West, as iconic as one of those portraits of Buffalo Bill in buckskins or that grungy tintype of Billy the Kid. On the other hand, it might have gone the way of his guidebook, which, aside from facsimiles or a hypothetical copy lost in someone’s attic, is nowhere to be found. What is certain is that if that errant glob of collodion had formed an inch to the right, I wouldn’t be writing about this picture on a Lovewell history website.

Anyway, back to serendipity. I’ve learned in the past few weeks that, far from being extinct, wet-plate collodion photography is alive and well, if not insanely popular. Not only are there several Youtube videos devoted to the technique, but there are a few chemical suppliers which specialize in selling ingredients to hobbyists.

So, if anyone out there has an 8 x 10" view camera gathering dust in a closet, plus a few hundred dollars in spare change to spend on a chemistry set, and one of your fledgling efforts turns out a bit like the picture shown above - please drop me a line and tell me what you did wrong. Until I hear something, I’ll have to be satisfied to keep guessing.

Photograph from the Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library