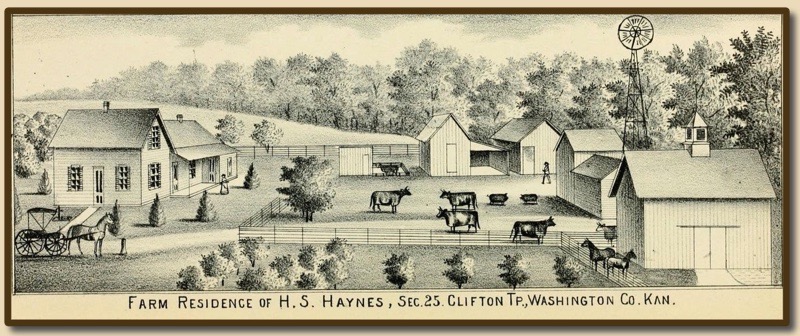

Studying the Lovewell family and their neighbors in the latter half of the 19th century required me to dive into a bunch of musty local histories. One of these was “A Portrait and Biographical Album of Washington, Clay and Riley Counties," published in 1890 and containing, to my surprise, a carefully composed drawing of the Hiram Sylvester Haynes farm near Clifton.

The “album" must have been the ultimate coffee table volume of 1890, chock full of engraved likenesses of U. S. Presidents and Kansas Governors along with details of their lives and accomplishments, sections which take up the first 150 of the book’s 1,254 pages, giving it the heft of something between a desktop encyclopedia and an unabridged dictionary. There are also a few fine engravings and life stories of local pioneers such as Gerat Henry Hollenberg, Thomas Lovewell’s neighbor along the Black Vermillion in Marshall County in the mid-1850’s, before he moved a few miles west to be the founding father of Washington County. Hollenberg had left Prussia to become a 49’er in California when he was in his twenties, then a miner in the Andes of Peru, and even explored the Amazon before being drawn to Kansas, where he is remembered chiefly for operating the Hollenberg Pony Express Station at Hanover.

The Haynes family had been among the first to come to America and may have been distantly related to the Lovewells. One of the few certain facts about the progenitor of the Lovewell line in America is that he married Elizabeth Sylvester at Scituate in 1658. A wife’s surname often survived in the names given to children in succeeding generations, and the first Haynes to strike out for the new West was Sylvester Haynes, who in 1817 settled near Little Hocking, Ohio, about forty miles from Nelsonville, moving on to southwestern Illinois in the 1830’s. John Griffin Haynes, the son of Sylvester and Susan Griffin Haynes came to Clifton, Kansas, in 1863, one year after the Homestead Act was signed into law.

John Griffin Haynes was the Washington County leader who appended his name to an open letter addressed to the Adjutant General of Kansas in 1864 requesting either military protection or arms, and also corresponded with Governor Crawford about Indian troubles in 1867 following the White Rock Massacre. His letter to Crawford may contain the only solid clue to the identities of a pair of buffalo hunters killed in the region in 1866 or 1867. His youngest son John Walter Haynes was one of the six victims of another attack in May of 1866, one that began with a desperate chase which Orel Jane Lovewell believed she had witnessed while the Lovewells and Davises were exploring their new neighborhood only a few days after arriving in Republic County.

The farm of Hiram Sylvester Haynes and his wife Diantha Melissa Gilbert Haynes, may have been the one where Vinson Perry Moore grew up. The couple from Clifton had been entrusted with the care of little Vinson, Orel Jane Lovewell’s son by her previous husband, when he wasn't staying with his maternal grandparents, who lived nearby. The picture, like all the drawings of farmsteads in the book, is highly stylized. Buildings are packed together much more densely than they would have been in real life, and are displayed with an exaggerated 3d perspective. Conversely, the artist draws farm animals as if he were adorning the walls of an Egyptian tomb. They are almost always presented in profile, horses hitched to carriages and either prancing gaily or patiently awaiting their master’s firm command or the gentle tickle of a lash along their flanks.

I wonder sometimes if the stories of grit and determination and the accompanying illustrations in these old books haven’t wormed their way into our collective consciousness by osmosis. They present us with a vision of the past as we sometimes imagine it, a world of perfect clapboard houses, manicured lawns, and obedient livestock. It is always spring. The buildings are all newly-shingled and freshly-painted. There is no such thing as recession or drought or blight or hog cholera. There is no obstacle that a little gumption won’t fix.

It’s hard to imagine the Haynes family forsaking such a perfect little Eden, but they did. Shortly after the picture album was published they began migrating to Pasadena.