We can state with some certaintly that throughout the summer of 1903 Thomas Lovewell was busy working on his mining claims about 25 miles southwest of Laramie. Apparently he and a select group of adventurous family members, accompanied by one or two neighbors, headed west in a small wagon train that set out from the village of Lovewell on April 14. It was to be a memorable season, beginning with a late spring snowfall that threatened to linger into summer, followed by an outbreak of debilitating fevers, and capped by a dynamite blast that destroyed Walter and Josephine Poole’s cabin, built two months earlier. And yet, the most memorable event to come out of the trip to southeastern Wyoming that year might have had nothing to do with weather or sickness or high explosives.

President Theodore Roosevelt had taken a three-week vacation in April to enjoy the wonders of Yellowstone, followed by a trip across the state at the end of the month with stops in Newcastle, Evanston, Laramie and Cheyenne. The President’s train traveled east across the Plains as far as St. Louis by the end of the month, before looping back for a visit to the West Coast via Santa Fe, and then returning to Wyoming, making a brief stop at Evanston on May 29.

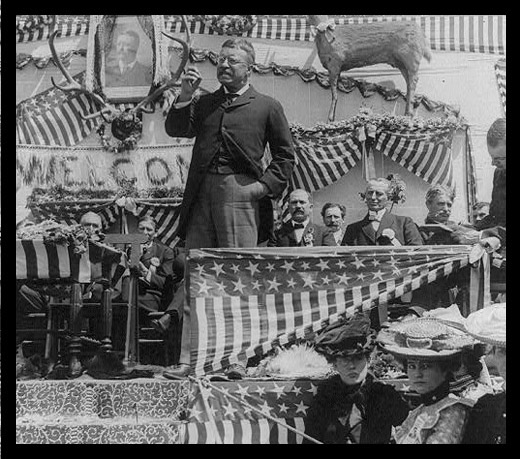

The next day Roosevelt spent 90 minutes at Laramie, delivering a speech at the University of Wyoming in front of a throng of perhaps three or four thousand rapt listeners. Living up to his reputation as an outdoorsman and man of action, Roosevelt then traveled by horseback from Laramie to Cheyenne at the head of a column of mounted dignitaries which included a U. S. Senator, several lawmen, and a prominent stockman. At the end of his ride, the crowd that gathered to hear him speak at Cheyenne was estimated at 10,000.

Did the prospectors from Kansas arrive ahead of all the pomp and circumstance? The answer depends on how long it would take a wagon train to reach Wyoming from Jewell County in 1903. For those unfamiliar with the territory, Lovewell lies just about dead-center in the northern tier of Kansas counties, about eight miles south of the Nebraska border, and nearly 500 miles from Laramie. We know that in 1908 Thomas and his son William Frank pulled into Laramie in a horse-drawn wagon on May 28, though we don’t know exactly when they set out from Kansas. Conversely, while we learn that they were back in Kansas around the 20th of August of that year - an early return, possibly owing to Thomas’s age finally catching up with him - there was no report in the Wyoming papers to tell us when the pair had left Laramie.

The closest thing to an accurate timetable might be provided by the aforementioned Jewell County delegation’s departure from Lovewell on April 14, 1903, followed by a letter home from Grant Lovewell published in the June 12 Courtland paper complaining that “it has snowed constantly for three weeks and he would prefer Kansas floods and sunshine to Wyoming’s snow and gold fields.” Assuming that the letter was mailed a week prior to publication, and Grant Lovewell saw snow begin to fall the moment the family’s wagon train arrived at Jelm, they could have passed through Laramie around the middle of May, leaving plenty of time before President Roosevelt’s impending visit at the end of the month.

Given the distance between Lovewell and Laramie, the wagon train would have had to travel only twelve miles a day, about what a Conestoga wagon pulled by two yoke of oxen covered on an average day during the Gold Rush fifty years earlier. Thomas Lovewell easily could have been among the thousands of spectactors lining the streets of Laramie to see President Roosevelt on May 30, 1903 - if had decided to take a break from his prospecting chores to be there. He may have done just that.

Thomas was a staunch Republican who in 1893 had traveled 25 miles to Mankato to hear an address by the Speaker of the Kansas House, inveighing against the evils of the People’s Party, who had handed the Republicans a drubbing at the polls. Bear in mind also that Thomas had named his eldest son, born January 23, 1869, “Simpson Grant,” in honor of the former Union general who would take the oath of office as President six weeks later. The eventual scandals of the Grant administration might have led Thomas to entertain second thoughts about the name, and the boy himself grew up to prefer being called “S. G.”

When Thomas Lovewell named at least three of his Wyoming mining claims “Rosefelt,” he was probably paying tribute to a Republican politician he admired, even if it was one whose name he couldn’t quite spell, a President who was determined to preserve the West both men loved. But Thomas also may have been reminiscing about his own brush with greatness on the streets of Laramie in 1903.

Historical photos of Roosevelt in Wyoming courtesy Library of Congress