Hannah Duston was not an overnight sensation. Although statues would be raised to her memory one day, in the months immediately following her thrilling escape from Abenaki captors, her only visible monument may have been the shingle John Lovewell hung in front of his house announcing that the returning heroine had slumbered safely under his roof. We know some details about Hannah’s ordeal and the terrible vengeance committed with the aid of her nurse and a young man the Abenakis had captured a year earlier, because she related the story to a diarist in Boston and to the Rev. Cotton Mather. The Puritan minister pronounced Hannah’s bloody retribution against the Indians a righteous act, and extolled her as a Puritan saint in his Ecclesiastical History of New England, published in 1702. The Rev. Mather and history did not deal so kindly with Hanna’s younger sister.

Hannah was the eldest of fifteen children born in the Emerson household at Haverhill, and one of the lucky nine who survived infancy. The townsfolk did not seem eager to have the Emersons as neighbors. When Michael Emerson had prospered sufficiently on his farm two miles beyond Haverhill that he could move his family within the town, the city fathers offered him a parcel of land if he would just stay in the woods where he belonged. Michael took the bribe, and the Emersons proceeded to to justify the town’s wariness about them.

Elizabeth Emerson must have been a handful, but even the rigid Puritans who looked favorably on corporal punishment thought the 12-year-old’s father went too far on at least one occasion. Michael Emerson was fined for “cruel and excessive beating of his daughter with a flail swingle and for kicking her.” It was a small fine, as fines went in New England. A pair of Haverhill girls had to pay ten shillings each for the crime of wearing silk, that is, for dressing above their station in life. Michael’s fine was a measly five shillings for trying unsuccessfully to beat the devil out of his daughter, and even a portion of that amount was forgiven. Another Emerson daughter, Mary, and her new husband were threatened with fines or a severe whipping when their first child was born less than 32 weeks after the wedding. Three years later, perhaps emboldened by Mary’s example, Elizabeth gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, Dorothy. We do not know what became of Dorothy, but what happened to two more of Michael Emerson’s unfortunate grandchildren became the talk of the town.

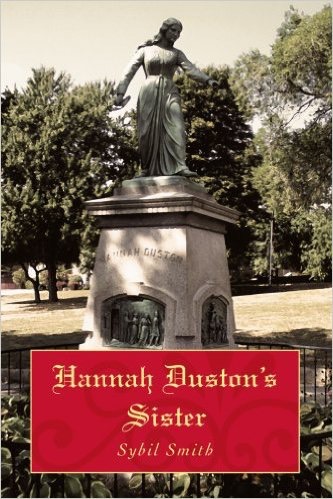

Statue of Hannah at Boscawen, N. H.

Photo by Craig Michaud from Wikipedia

Five years after delivering a fatherless daughter, 26-year-old Elizabeth Emerson secretly gave birth to twins in the dead of night as she lay in the trundle portion at the foot of the bed where her parents slept. Either the babies were both stillborn, or one was, and she snuffed out the life of the other before placing their bodies in a trunk beside the bed, taking them outside for burial three days later. A delegation of suspicious housewives showed up at the Emerson farm with a warrant to examine the young woman, while men searched the grounds until they uncovered a small grave. One of the women who could testify that Elizabeth Emerson had recently given birth was Mary Neff, who would be Hannah Duston’s nurse and fellow captive six years later. Found guilty of infanticide in an age when even concealing the birth of a bastard child was a capital crime, Elizabeth Emerson was sentenced to be hanged. In 1893, shortly after a visit from the Rev. Mather, alighting fresh from the Salem witch trials in time to hear her confession, Elizabeth was hanged from the hanging tree in Boston Commons, along with a black woman sentenced for a similar crime.

Not only did Hannah Dustin become an American folk hero, but she redeemed the honor of the Emerson Family. She was the 40-year-old wife of Thomas Duston when she was dragged from her bed by Abenaki raiders a week after giving birth to her ninth child, and was forced to march north with baby Martha, Mary Neff, and about ten other captives, who were told they would endure humiliating torments before being handed over to the French to be ransomed. Behind them, 27 of their fellow English colonists lay dead inside their blazing homes. At the very start of their trek, one of the Abenaki abductors snatched baby Martha from Mary Neff’s arms and dashed her head against a tree. It was the moment that seemed to justify everything Hannah did afterward.

In the 1800’s Hannah’s name was again on everyone’s lips when Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, John Greenleaf Whittier, and others took turns retelling her story, each writer emphasizing particular points to cast a different light on her bloody deed. In Hawthorne’s version the Abenaki victims were the tale’s true innocents, Hannah’s husband was a “tender-hearted, yet valiant man,” while his famous wife was “a bloody hag” and an “awful woman.” As is true with many of history’s luminaries, whether we see Hannah as a vengeful heroine or a blood-craving monster depends on which details a writer chooses to omit, or which dots a reader decides to connect on his own.

In making her a Puritan saint, the Rev. Mather notes only that she slew ten savages (or “salvages” as he puts it). Does it change our opinion of Hannah to know that the Abenakis were in fact Catholics (A detail that might have made Mather wish they had been tortured before death) or that Hannah and her two English companions were exterminating a family? Writers who want to score points for Hannah sometimes refer to her victims as two men, two women, and six “others.” Killing two women and seriously wounding a third might seem more ruthless to us if Hannah had been a man, but does it give us pause to realize that the “others” were children?

Was it with any sense of irony that Mary Neff, who had helped to put a noose around the neck of Elizabeth Emerson over the deaths of two babies, watched, helped, or at the very least abetted in the slaughter of three times as many young Abenakis as they slept? Did anyone think less of Hannah for pausing in her escape to go back and scalp all ten victims? She said she was afraid that she would not be believed unless she had evidence, even though her story could be verified by two witnesses. What’s certain is that having the scalps enabled her to collect a generous bounty. There’s a difference of opinion about how much money Hannah got, but the smallest amount named was 25 pounds at the outset, with more to follow from private donors. Years later she asked for a pension for her service, and apparently received it.

Judging from the story of the Emersons and the early history of Haverhill, Hannah was raised in a particularly rough family during a violent era. Treated brutally by her captors, she responded in kind. If there is one more thing we wished to know, it might be what went through the mind of the young man in the Lovewell house the night Hannah Duston slept there, the five-year-old who would grow up to be celebrated in story and song as “worthy Captain Lovewell.” Did he remember meeting the nice lady with her smelly parcel stuffed full of scalps?

For the story of Hannah and Elizabeth, complete with their inner thoughts and salient details no one could possibly know but might really like to, read the 2005 page-turner “Hannah Duston’s Sister” by Sybil Smith. Better than Hawthorne.