I count on Dave Lovewell to catch anything I’ve missed, and he never lets me down. Dave points out that David Crockett would have worn one more critter on his head when he was wandering around Washington City in his fancy duds - a beaver. Beaver hats were the rage in Europe for 300 years, causing the near-extinction of the American beaver’s Eurasian cousin. The demand for pelts from the New World created mighty fortunes for a few men such as John Jacob Astor, and a livelihood for trappers and traders, among them, three who would later be Thomas Lovewell’s neighbors in Kansas Territory, Julian Gingras (Known in area histories as “Changreau”), Louis Tremblé, and James McCloskey.

Dave also reminded me of something the Jeopardy anecdote I recounted last time should have made clear: Davy Crockett is today a hazy outline of a man with a familiar name. When people do write about him it is generally to challenge the authenticity of his coonskin cap. The cap, which some writers maintain that he never wore, has become better known than he is. People really have forgotten who David Crockett was.

By the time he died at the Alamo at the age of 49, Crockett may have been the most famous man in North America, a sort of cross between Daniel Boone and Elvis. Some writers consider him the first modern celebrity, someone who is celebrated largely for being widely known and spoken of around the water cooler.

The appraisal seems somewhat unfair, because David Crockett set out to make something of himself, and managed to do so, even if he never got rich doing it. Born to a poor farmer who also ran a mill and a tavern, young Crockett not only helped out around the farm, and worked in the mill and the tavern, but was sometimes rented out as a drover or laborer to pay off the notes his father’s creditors were holding. Becoming an expert marksman, renowned hunter, and eventually a colonel in the militia, Crockett decided that his marital prospects were limited by his lack of education, and agreed to work for a Quaker teacher for six months in return for lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

His improved literacy not only won a bride, but qualified him for a position as local magistrate. A few years after his first taste of public office, he was elected to the state legislature. He campaigned for Congress and lost, tried again and won. The Whigs briefly toyed with the idea of putting him on the ticket as a presidential candidate to challenge Andrew Jackson.

Crockett had a few rough edges which were ignored when he was portrayed by 29-year-old Fess Parker on “Disneyland” in 1954. He owned slaves and sometimes sold one or two when he was strapped for cash, which was most of the time. After the death of Mary “Polly” Crockett, he married a widow with two children, desperate for someone to look after his own three. David and Elizabeth would add three more offspring to the family before the second Mrs. Crockett moved out of the house to live with her relatives, fed up with her husband’s drunkenness, dalliances and chronic debt. He did try to make amends, giving up drinking and skirt-chasing, or at least cutting down on both. Hoping to improve his finances, he turned to writing his memoirs with the help of his Washington roommate Thomas Chilton of Kentucky, who may have smoothed out his friend's grammar and punctuation, but took care to preserve Crockett’s authentic frontier voice. What the two men produced not only flew off the shelves, but became an instant and enduring classic.

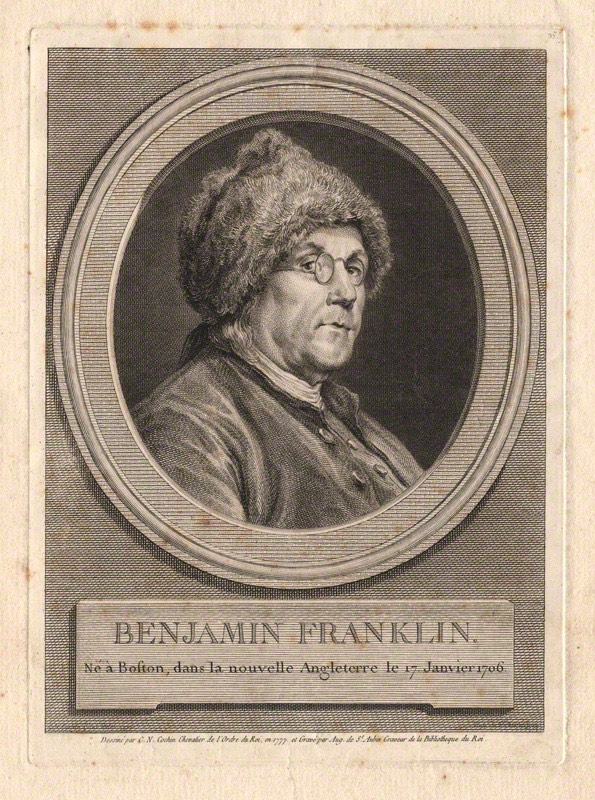

The model for Crockett’s best-seller may have been Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, one of the volumes the frontiersman is known to have owned. Ironically, there was never any debate concerning Mr. Franklin's coonskin cap. Several paintings of the Founding Feather testify that he wore one habitually. Another book bearing David Crockett’s name on the flyleaf, one which he seems to have consulted while gathering his thoughts, was Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Crockett never stopped being a country boy, but he was no bumpkin.

He also fought battles which continue to endear him to biographers. He tried to get bills through Congress to reduce taxes and allow squatters along the frontier to receive lawful ownership of the federal land they had been farming and improving year after year. He also split with Andrew Jackson, his old commander during the Creek Indian War, over the Indian Removal Act, or “oppression with a vengeance,” as Crockett called it. As with most of his political battles, this is another one which Crockett would lose. A quarter of the Cherokee Nation perished along the Trail of Tears between Georgia and Indian Territory, while David Crockett headed to Texas to meet an end that would seal his fate as an American legend.

His death at the Alamo in March of 1836 must have taken the whole country by surprise - one of those moments when everyone remembers where he was and what he was doing when he heard the news.

Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain were among Crockett’s admirers. Even Edgar Allen Poe mentioned him a couple of times in the course of reviewing other people’s books. While discussing a scene in “Norman Leslie: A Tale of the Present Times,” in which a lady faints when the cad she has secretly married flashes a smile at her, Poe announced that Davy Crockett had been outdone. “Thou has indeed succeeded in grinning a squirrel from a tree, but it surpassed even thine extraordinary abilities to smile a lady into a fainting fit!”

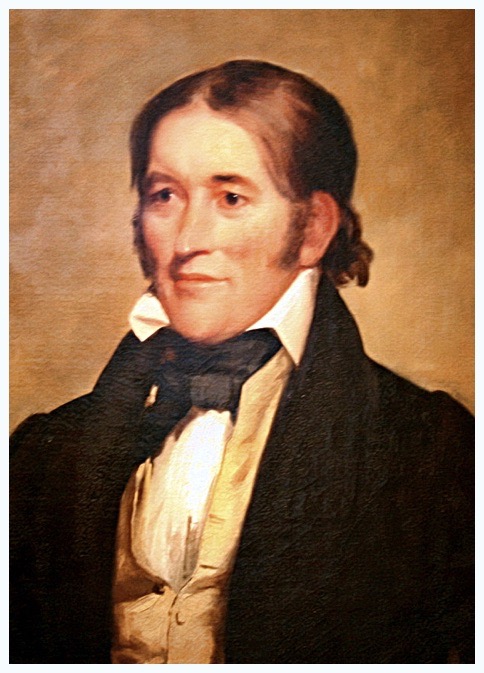

I don’t know. Judging from his portrait at the top of the page, you have to wonder if he might’ve been up to it.