I do like history, but know enough to be grateful that I don’t live there. The thought ran through my mind as I marched briskly for a distance of about three blocks up the street Sunday evening to bring home snacks from Taco Bell for Oscar night. Nothing but the best for the family. A winter storm was raging. There was a crunchy layer of sleet underfoot. The temperature was ten degrees above zero, but a howling north wind drove the wind chill into the minus column and pelted my face with snow.

I kept thinking of a section of Eugene Ware’s book on the Plains Indian War I read a few nights ago, about a scouting trip along the Republican River late in January of 1865. Someone had thought to bring along a thermometer to validate the men's suffering, and one night the mercury dipped to twenty below. They built several fires and never strayed far from one, hoping to ward off frostbite.

The wind came down from the northwest with the fury of a cyclone, and it blew the ashes from the fire so that, although we had large log-heaps, we could only stay on one side of them with the wind blowing on our backs; we could only get warm by hugging the fire. As the night grew on it became dangerous to go to sleep. The horses were taken into the most sheltered part of the woods, and fires were built in log-heaps some little distance from the horses to the windward, so that the warmth would blow down onto them. Nobody went to sleep that night. The guards were changed every thirty minutes, and the men brought in.

Everybody kept in motion, nobody dared to go to sleep, and although we had log-heaps blazing, it seemed almost impossible to keep from being frost-bitten. Finally the wind ceased in the morning as the sun rose, and it rose clear and still. What such a streak of weather would do for the Indian fleeing across the country we could well imagine. It carried out Bridger's theory of the death of the women and children if the chasing of the Indians continued during a winter campaign. An Indian campaign in the winter is anything but pleasant. There is absolutely no fun in it.

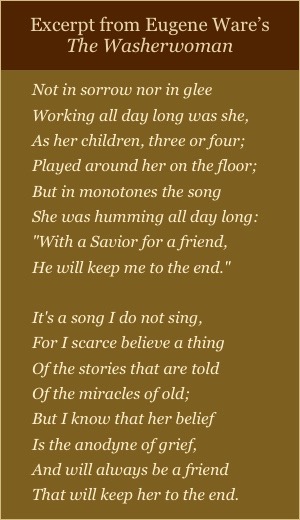

Eugene Ware was a Kansas newspaper editor, lawyer, politician, and poet. His rhymes were published under the pen name “Ironquill,” although their author’s identity was no secret. They are sometimes mysterious and brooding, in other cases whimsical.

He also translated the Emperor Justinian’s Codex from Latin to produce a book on Roman water law. Ware’s military memoir was not published until shortly before his death, forty-five years after his service on the Plains. Yet, he did not see his Army years through any haze of nostalgia. He not only kept a journal but faithfully wrote letters to his mother, and, as mothers tend to do, she had carefully preserved them.

When he wrote about a scout made in January along the Republican River, he worked from detailed notes which reminded him of exactly how it had felt, and which two of his fingers had been frosted, the two front fingers of his left hand. He wrote with a poet’s meticulous choice of words, making us feel the cold of a Plains winter in our bones.

As I started to make my way homeward carrying a bag of warm burritos Sunday evening, I decided to put a gloved hand in front of my face to deflect the wind. No telling how quickly frostnip might set in on a night like this.