There’s a Neil Simon comedy by that name that was made into a 1970 movie starring Jack Lemon and Sandy Dennis. I have friends who find it amusing, but for me it’s no more than a catalog of muggings, kidnappings, chipped teeth, sudden downpours and other calamities that beset a couple from Ohio visiting the Big Apple during a sanitation department strike. I did not laugh once as I watched a print of the film unspool in a Pomona movie theater. I might congratulate myself at not being afflicted with what Germans call schadenfreude, pleasure in the misfortunes of others, if I didn’t find what happened to the Akerlys on the Plains of Kansas in 1869 absolutely hilarious.

A few new details about their bogus journey have come to light because of Phil Thornton's recent excellent adventure in Washington, D.C. Phil said he had to be there anyway for a conference and stayed an extra day, spending it at the National Archives, going through Indian depredation case files. Thanks to an Act of Congress, settlers who could prove measurable losses to Indian tribes “at amity with the United States,” might recover damages. They might, but seldom did. Those strict conditions, a provable loss, one that could be measured in dollars and cents, suffered at the hands of members of an identifiable tribe that had signed a peace treaty, almost never came together.

The claim of a father who demanded $5,000 for loss of his daughter’s innocence was automatically disqualified. Thomas Lovewell’s friend John Griffin Haynes may have hoped to be compensated for the loss of his youngest boy Walter, killed in an 1866 attack, but could only sue for the value of the rifle Walter carried on his ill-fated buffalo hunt. The Ackerlys, on the other hand, could itemize everything they lost and calculate its worth. There were witnesses to the raid that deprived them of all their worldly goods, and the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors who had bedelviled settlers in Jewell County the whole previous week, left plenty of calling cards.

The newlyweds and a companion named Walter Jackson departed New York on May 1st to join their fellow members of the Excelsior Colony at the group’s headquarters eighteen miles west of White Rock. They arrived on the scene three weeks later, received news of a recent Indian massacre a few miles northwest of the colony’s makeshift fort, and immediately made plans to head home. Ernest Ackerly offered brothers William and Frank Frazier $50 to haul them and their possessions back to Washington County, where they could catch an eastbound train for New York. Threatened with attack from hostile Indians, they chose to leave the shelter of the Excelsior stockade and the company of sixty of their friends armed with muskets. No, Ernest Ackerly decided, this was no time for caution, but a situation that called for an immediate road trip. What could possibly go wrong?

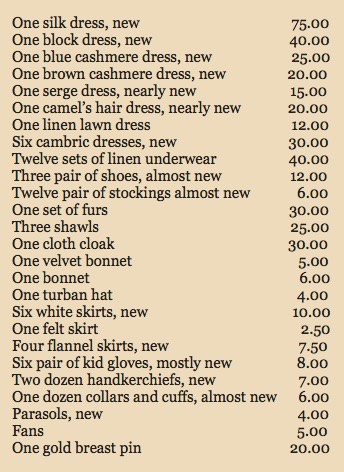

William Frazier’s team had pulled the wagon about eight miles eastward when between 80 and 100 Indians swooped down from the hills to the north. The brothers unhitched the horses, told their guests to head for cover along White Rock Creek as soon as the Indians were out of sight, and galloped away to warn the colony of an impending attack. The Indians pursued the two riders, giving the Ackerlys and Jackson time to hide in the brush before some of the raiders doubled back to rifle through the boxes in the wagon and make off with their valuables. When the Indians surrounded the Excelsior fort later in the day they and their horses were decked out in some of Mrs. Ackerly’s finery. According to the depredation claim, there was plenty to go around.

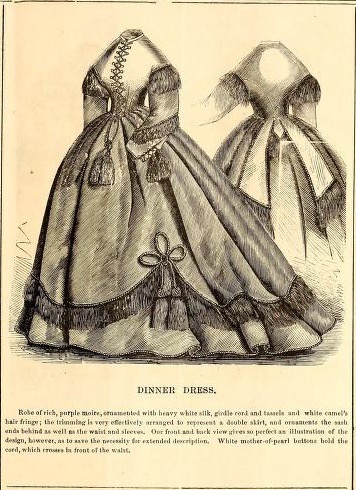

It must have been quite a fashion show at the Excelsior fort. Although not completely accurate, Winsor and Scarbrough’s “History of Jewell County” picks up the story of what became of the Ackerlys after the Indians left the area and the sun went down.

The husband and wife at the wagon, with two Englishmen who belonged to the Colony, ran down John's Creek, and assisting the woman, crossed the swollen White Rock, and escaped, reaching Lovewell's at 3 a.m., the next morning. In their flight they followed every tortuous bend of the stream, not daring to cross the open spaces for fear of being seen and butchered by the Indians. The woman was a sad sight to look upon when she arrived. Having had to cross the stream several times, in order to facilitate her flight, she had taken off all her clothing but one dress, her petticoats being so heavy with water that she could not walk with them on.

The full inventory of their losses included seven suits for Mr. Ackerly, two overcoats and a dozen shirts, as well as some cooking utensils. One has to wonder what sort of place Ernest and Mary Ackerly thought they were headed for on the Kansas frontier. Even if there had been no Indians on the loose, would the couple have lasted longer than a month? There would be later, more successful Excelsior colonies, but after one nervous run-in with Tall Bull’s Dog Soldiers, the one that arrived in the spring of 1869 immediately disbanded. Some, like the Ackerlys, realized that they were completely out of their element, out-of-towners ready to beat a hasty retreat back to Gotham.