Several months ago I happened upon a newspaper cartoon celebrating historic events in rural Kansas. The drawing focused on a small band of Buffalo Soldiers who tremble with fear at a spectral image presumed to be poor, mad Mary Ward, captured in the recent Jewell County Massacre, haunting a moonlit prairie.

Drawn in the 1940’s in the style of a “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” panel, the cartoonish soldiers resemble figures from those “Merrie Melodies” shorts that can make us wince during their thankfully rare appearances on TV these days. If you don’t recall them, imagine a 1930’s depiction of a valet who has just seen a ghost and his eyes are about to pop out of his head. Now imagine several of them, all dressed for a Civil War reenactment.

The drawing was the latest item that turned up in my search of the Kansas press for stories about the White Rock Massacre and Buffalo Soldiers. It stood in sharp contrast with photographic images of actual Buffalo Soldiers on the National Parks website.

The rugged group assembled at a campsite could be the cast of a hitherto unknown Sergio Leone Western on their lunch break, or a publicity still for a 21st century remake of The Wild Bunch.

One of the family tales about Thomas Lovewell’s experience scouting for men of the 10th Cavalry in 1867 is borne out by the history of the regiment. Lovewell found the soldiers undisciplined, likely to whoop and holler as they broke ranks to chase a bolting jackrabbit when they were supposed to be quietly trailing an elusive foe.

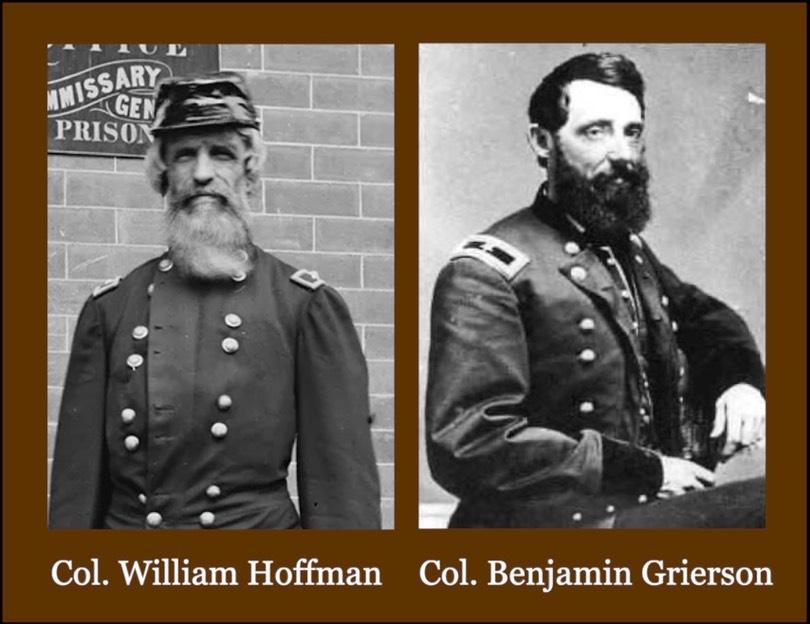

According to a master’s thesis written by Major Anita Williams McMiller, the root of the problem lay in the leadership provided at Fort Leavenworth, where the men trained before deployment. The 10th was commanded by Col. Benjamin Grierson, a music teacher in civilian life, who culled unsuitable recruits and established a rigorous program of drills.

Company “A,” under Grierson’s oversight, forged an enviable reputation on the frontier. Unfortunately, Grierson was called away to his father’s deathbed before “B,” the unit Lovewell knew, was ready to take the field. With Grierson out of the way the job of training black recruits was overseen by Col. William Hoffman, who had clashed repeatedly with Grierson and took every opportunity to disparage the African-Americans troopers he commanded. The two men almost came to blows on one occasion, after which Hoffman tried to have Grierson court-martialed. His superior officers only laughed and shook their heads.

Once their commander was out of sight, Hoffman seemed to push all black recruits out of Leavenworth as quickly as possible, ready or not. The partly-trained men of “B” company under Lt. John Myrick joined men of the 3rd Infantry under Captain Daingerfield Parker at White Rock, with Thomas Lovewell as their scout. If the experience was disappointing for Lovewell, it was worse for Buffalo Bill Cody, who had to contend with scouting for a completely dysfunctional “C” Company, whose pickets tended to shoot first and only remember to issue a verbal challenge afterward. Fortunately, their aim was often poor.

While men of the 10th Cavalry were engaged in a number of desperate fights and would quickly prove their mettle on the Kansas frontier in the late 1860’s, their deadliest foe was an outbreak of cholera that tore through Army outposts with lightning speed. Soldiers and civilian personnel who woke symptom-free might be lowered into the ground before evening fell.

Chronically malnourished men such as those who joined the 10th Cavalry were hit especially hard. By some estimates, of the three companies of Buffalo Soldiers who rode out of Fort Leavenworth in the spring and summer of 1867, one man in ten would be dead by winter.

When he returned, Col. Grierson managed to have the 10th Cavalry transferred to Fort Riley, away from Hoffman’s iron thumb. Col. Hoffman retired in 1870.