While leafing through Rhoda Lovewell’s updating of the family story, I was pleased to learn that she has independently come to the same conclusion I reached only about two years ago, regarding the Lovells. Although they could be related to the Lovewells, we can’t be sure just why or when one line branched off from the other. Rhoda zeroes in on Robert Lovell’s son John, who married Jane Hatch and whose son John was born in 1658, the same year a tanner who gave his name as "John Lovwell" married Elizabeth Sylvester at Scituate, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, to some, the writing of John’s surname looked more like “Lowwell,” leading to generations of genealogical confusion, none of it having anything to do with John Lovell, who was someone else entirely.

Yes, there were evidently three men about the same age with similar names in the same part of Massachusetts, who were sometimes mistaken for one another on official documents and in family trees. A fog of doubt settled over me until I found a volume called “Soldiers in King Philip’s War,” published in 1891. All three men are listed, with their names spelled the same way we spell them today: Lovewell, Lowell, and Lovell. Dovetailing with Lovewell family tradition, only John Lovewell is listed as a veteran of the Narragansett campaign, in which, as legend has it, he took part in the Great Swamp Fight (If you’ve never heard of it, rush out and buy a copy of Nathaniel Philbrick’s “Mayflower,” which contains a spellbinding account of this bizarre battle).

New England historian Ezra S. Stearns took pains to untangle the lives and offspring of John Lovewell the tanner from John Lowell the cooper. However, Stearns apparently had never heard about that other matter, an effort by some Lovewell family members to splice together John Lovewell of Dunstable and John Lovell of Barnstable.

It must have seemed a logical step. It appears that few people pronounced “Lovewell” as a distinctly two-syllable word. Not only do some antique maps of Colonial New England identify an historic body of water which was the scene of an Abenaki ambush as “Lovel’s Pond,” so does the stereoscopic photograph taken there in the late 1800’s and shared below (cross and defocus your eyes for a breathtaking stereoscopic thrill at your own risk).

People quite familiar with the Lovewells sometimes got the family name wrong. A newspaper reporter cautiously making his way into Republic County during the Indian troubles of 1869 wrote about reaching “Lovel’s at White Rock.” In her correspondence with pension agents, even the slain Christopher Lovewell’s widow Martha Jane sometimes spelled her late husband’s surname as “Lovel.”

Kansas scientist Joseph Taplin Lovewell was so sure there had to be a connection between the Lovell and Lovewell families, that on his Sons of the American Revolution application he listed his most distant known ancestor as “Robert Lovewell.” If he was actually referring to John Lovell’s father, the “husbandman” who brought his household to Massachusetts aboard the Marygould in 1635, he would not be the last Lovewell family historian to make that mistake. Gloria Lovewell, author of the 1979 edition of “The Lovewell Family,” half-heartedly went along with a notion, apparently proposed by amateur genealogical sleuth Sherman Lee Pompey, that Jane Hatch had been the first wife of John Lovell, who, two years after the birth of his son John, married Elizabeth Sylvester, kept houses simultaneously in northern Massachusetts and on Cape Cod, fathered a second son named John (along with several more children), and commenced to spell his family name differently. Sure, it sounds farfetched if you put it like that.

Well, Rhoda’s having none of it, although her newly-revised and vastly-expanded history book still begins with a dissertation on the Lovell name, evidently meaning that she agrees that the Lovells and Lovewells are intertwined, even if there’s no way of sorting out quite how. She does clear up another matter for me - who the heck Sherman Lee Pompey was. Along with the monumental task which is just now receiving her finishing touches, Rhoda inherited a folder stuffed with correspondence from Mr. Pompey, who turns out to have married the great-great-granddaughter of William Lovewell and his third wife, Matilda Wise. Actually, Pompey's connection with the Lovewell family was waiting to be discovered in Gloria Lovewell’s original version of the family story, if I had managed to stay awake through the begats on page 160. Apparently, I did not.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Thomas’s brother Solomon was named after Solomon Lovell, who was a brigadier general in a Massachusetts militia during the American Revolution. Solomon Lovell was a great-great-grandson of Robert Lovell, whose descendants settled in Barnstable, far away from those Lovewells who congregated around Dunstable. Although I still think Solomon Lovewell probably was named for the Revolutionary hero, it’s even more likly that Moody Bedell Lovewell named at least two of his other sons after Lovells from Barnstable.

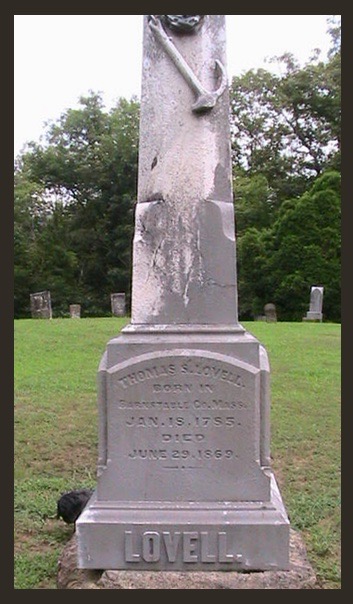

Perhaps Moody’s most-celebrated neighbor in Athens County, Ohio, was the former sea captain Thomas S. Lovell who sailed the schooner Maria from Marietta, Ohio, to Baltimore in 1816, laden with pork, flour, and lard. Thomas was another descendant of Robert Lovell, a couple of generations further removed from Robert than his cousin Solomon was. Thomas Lovell’s father was Christopher Lovell, born at Barnstable in 1750. Thomas, Solomon, Christopher. It could be coincidence, but probably not.