Looking over my last post (“Show Me Where It Hurts"), I seemed imply that Thomas Lovewell was guilty of pension fraud. I didn’t mean to. He had earned his $12 a month honestly.

By 1891 he had reached an age that was almost twenty years beyond what the average American male could expect to attain. His hands and almost every other part of his body hurt. His joints were swollen. He had labored as a riverboat roustabout during his youth, worked his own farms for another thirty years while plying his trade as a stonemason and building contractor, served three stints as a frontier scout, and put in nearly two and a half years in the infantry. At the age of thirty-five he had walked to California, and then walked home again when he was forty. He could still stand tall when he wanted to, and could keep up a brisk pace, but probably steadied his gait with a walking stick.

Thomas was sure he had rheumatism and had suffered from it since his Army days. In 1891 the word was a blanket term for all sorts of body aches, and newspapers were rife with dire warnings about rheumatic fever, an ailment that could take root in the cartilage between bones and spread to the heart. He may have first noticed tenderness in his own joints when he was in his late thirties, about the time he was stricken with camp fevers in Fort Humboldt and Fort Churchill. The fevers had subsided and his lungs cleared, but now he could feel the pain migrating from his extremities to his chest, gripping his heart like an iron fist. If Thomas Lovewell was guilty of anything, it was morbid self-diagnosis. Knowing that, soon to turn 66 years old at the end of 1891, he still had nearly a third of his life ahead of him, we might conclude that he suffered from advanced arthritis, plus chronic heartburn.

He was always one of the lucky ones. He narrowly survived his military service, his farms generally prospered, and against all odds he had even stashed away something for a rainy day. However, anyone who had been around as long as Thomas Lovewell could see the signs that thunderclouds were gathering. Unfortunately, they were not the kind that brought actual rain. Drought maintained its stranglehold on the Plains and the Southwest. Crop failures, railroad overbuilding and bad debt were about to send the nation's economy hurtling off the rails. Yes, he enjoyed the life of a prospector, but Lovewell may also have believed that striking out for the West and finding gold was his best chance of securing a future for his family. In case he met with an unfortunate accident on one his expeditions, the Civil War pension was a modest safety net.

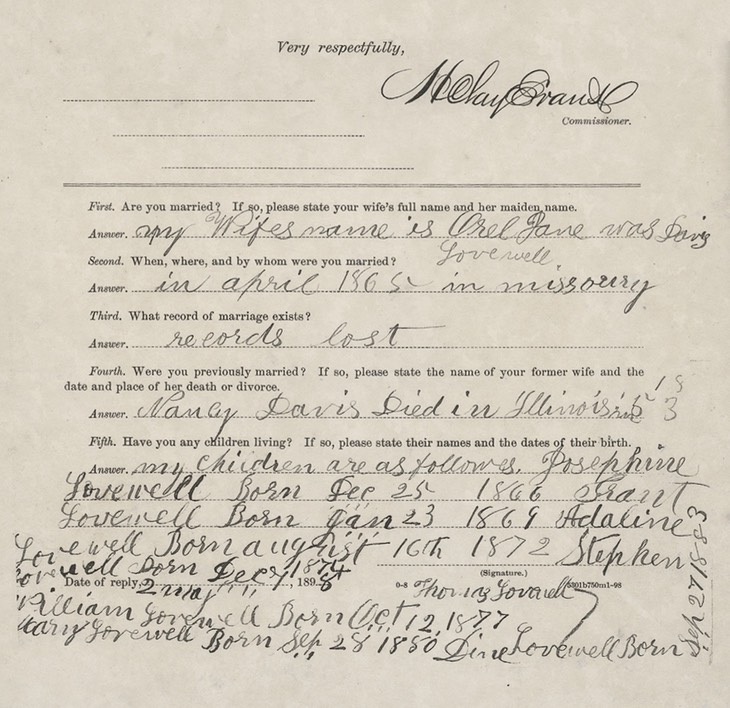

In 1898, months before he headed to Alaska where the nation’s newest boomtowns beckoned, Thomas Lovewell filled out another crucial pension form naming his dependents, listing his children's birth dates, and giving a simplified (And misleading) sketch of his marital history. This was important because two persons listed on the form might have received a quarterly settlement if he never returned from America’s final frontier. Diantha Desdimona “Dine” Lovewell was only fourteen when her father planned his most ambitious prospecting adventure yet. She was a shoe-in for an orphan's share. For his wife to receive payments as his widow, the Bureau of Pensions might demand some evidence that she was entitled to it.

This was why Thomas specified that he had married her in “Missoury” in 1865, and alleged that “Nancy Davis died in Illinois in 1853.” It was why he always listed his previous home states as California and Missouri, never Iowa, where he had lived on three occasions. It was better if the Bureau of Pensions didn’t hear about Iowa, where he had left his first wife in 1859, the state where she had filed for divorce five years later but hadn’t followed through. Thomas might even have written about the death of Nancy in 1853 with a clear conscience. There were rumors of a daughter named Nancy, who may have perished as an infant just before the Lovewells left Illinois for Iowa.

In 1898 Thomas could not have known how zealously pension agents would pursue cases coming up for review in the following decades. By 1907, the 1890 Pension Act had cost the country a billion dollars. In 1870 only 5% of veterans received compensation for their wartime injuries. By 1910, 93% of former Union soldiers received payments for a constellation of disabilities that included simply being older than 62.

Remarkably enough, the checks are still being written today. After the death of a 94-year-old pensioner last summer, an elderly lady in North Carolina, the daughter of a man who fought on both sides in the conflict, is the final recipient of VA benefits related to the Civil War.