My web-hosting service reminds me with a bill due every September that another milestone has been reached, and it’s time once again to take stock and consider whether it’s worth the trouble (not to mention a few dollars) to maintain a website devoted to family and regional history.

There have been a few changes to the site lately. Faithful visitors may notice that the old music page is now missing. Apple’s decision to offer a subscription music service tinkered just enough with iTunes to render my links inactive (oddly enough, until I pulled the plug they worked a bit better than before on some iOS devices). The main reason for having such a page in the first place was to give the curious a quick sample of those creaky New England ballads about Captain John Lovewell, which are now readily available from other sources, including Youtube.

Other than that, the main news is that web traffic is up. The stats page which tabulates the number of visitors per month, has sometimes tiptoed close to the one-thousand mark, without ever quite reaching it before. Last month’s count was 1,235. The number of page views was also a record, 3,174. Unique visitors numbered 499, not quite an all-time high, but very close to the June tally of 508, a month which also used to hold bragging rights for highest number of visits, at 953.

Why the uptick? I’m pretty sure I know the reason, or perhaps, the reasons. For one, the parents of our TV station's news director, Kristi, have enjoyed camping at Lovewell State Park the past two summers, and this time around her mother admitted to making an effort to talk up the Lovewell website with other vacationers, as well as the locals around Superior, Nebraska. Kristi’s mother is evidently quite persuasive.

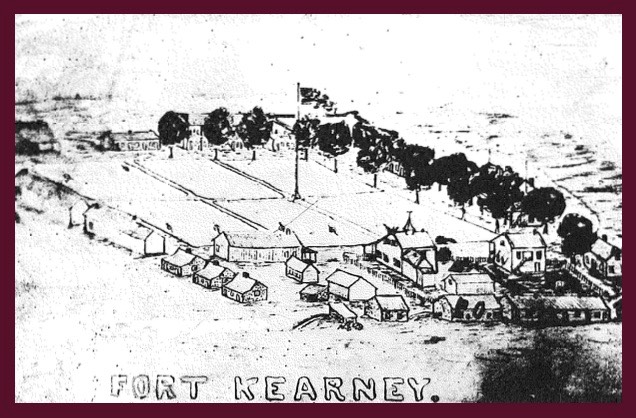

There’s also a Lovewell descendant and researcher named Vern Howe who inquired about re-posting some of the material from this site on Wikitree, which I assured him he’s welcome to do. At least part of the sudden spike in analytics probably owes something to Mr. Howe, as well. I haven’t visited Wikitree in a while, but sorting through old emails reminded me that I had made some inquiries there a couple of years back while looking for information about Hiram Creighton, the commissary sergeant who died at Dan Smith’s Station near present-day Gothenburg in May of 1865. Readers might recall that fighting broke out there only hours after Thomas Lovewell walked out of the station, bound for Fort Kearny.

Thus, the incident at Dan Smith's provides the one ironclad historical marker for Thomas’s return trip after his six-year-long sojourn in the Far West. I must get up to Gothenburg one of these days and have a look around - not because I think Thomas Lovewell may have dropped something along the way, but because the soldiers’ barracks where he bunked for the night is evidently still standing - but who knows for how much longer? There also could be an interesting detail or two waiting to be discovered in an application for a pension filed by Hiram Creighton’s mother in 1880. I’m at least curious to know what she knew about the running battle in which her son was mortally wounded. By the way, Hiram Creighton was 43 when he died from his wounds on the night of 12 May 1865. It might be worth reading the pension papers just to find out how old Mom was when she filled out that pension form fifteen years later.

Although I’ve written before about the incident at Dan Smith’s, culling most of my information from James E. Potter’s 1984 article from Nebraska History (see “A Trim Reckoning), I see that a pdf of Potter’s “A Medal of Honor for a Nebraska Soldier: The Case of Private Frances W Lohnes” is now available to download or read online (clicking on the title will whisk you there). The full tale of Lohnes’s military career, his courageous fight on May 12, 1865, his subsequent desertion, and the terrible circumstances of his death nearly a quarter of a century later, all make for an utterly absorbing story.

One of the few amusing aspects of Lohnes’s public life was that hardly anyone, even people who knew him well, could remember how to spell his name. I discovered this for myself several months before reading Potter’s account, when I was searching through 1865 military post returns from garrisons along the Platte River Road. Eventually it dawned on me that three soldiers whose names started with “L” all had to be the same man. The incident described by each source bore so little resemblance to the others, that, except for the various misspellings of “Lohnes” each one contained, they gave the impression of being reports of a series of unrelated attacks taking place along the Platte during the second week of May, instead of one protracted fight.

It transpires that three groups of soldiers stationed at different forts all stumbled into the fight near Dan Smith’s Station at various times on May 12, and all three reported the situation quite differently when they returned to their respective headquarters. One thing they could all agree on, apparently, was that the fellow whose last name started with “L” deserved sone kind of medal. So he got the highest one available: the Congressional Medal of Honor. Surrounded by ten attackers, wounded in the thigh and the shoulder, the stock of his Enfield rifle split by an arrow, Lohnes fought on until the rest of his unit could join him. Despite the fact that he deserted a few months after the medal ceremony, and after four years of continuous military service, the Army was willing to overlook his one lapse.

The stain of desertion would be removed posthumously from the hero’s record, so his widow Mary could be granted a pension which she would receive for the next thirty-six years. Given the chance to write about such things while making terrible puns - who could give that up?