I was delighted a few months back to discover the story of Arley Meek, a Kansan whose biography seemed to play out in a string of vintage press clippings. Fifteen items from various local newspapers dotting a large swatch of the state between 1903 and 1916, describe a young man’s ups and downs (mostly downs), but also reveal his knack for bouncing back from adversity with undiminished optimism.

Once I was sure that all of the snippets referred to the same young man from Courtland, Kansas, I began to see Arley Meek as a version of the wide-eyed Everyman personified by silent screen comedian Buster Keaton. Keaton’s heroes tended to underestimate the dangerous complexities of their world, making naive missteps that quickly cascaded into chaos. It was much the same for Arley Meek.

In most of the stories about Arley he’s either kicked by a horse and laid up for a few days, or dashed to the ground in a carriage accident. When the vehicle was demolished Arley gamely tried to repair it himself, smoothing over the rough spots with a fresh coat of paint before throwing in the towel and buying a new carriage.

Arley’s misadventure one evening in 1905 involving a violin and a horse-drawn sleigh on a bridge, should have been turned into a classic Buster Keaton one-reeler. A year later, hearing a town clock strike 3:00 a.m. on his first night in a Salina boarding house, Arley stuck his head out the window and mistook a passing cab for a fire truck. He rousted all of his fellow residents and led them on a frantic chase for several blocks in pursuit of an imaginary blaze. There was no funny climax to the story, merely a crowd of fuming boarders groggily trudging back to bed at four in the morning, and then making sure the tale of their disrupted night’s sleep was featured in the evening paper.

Arley was married briefly in 1912, filing for divorce the following year. The problem with the marriage apparently had less to do with personal incompatibility than with Arley’s house, or lack thereof. Robert Meek, Arley’s grand-nephew tells me that Arley’s new bride may have been horrified to learn that she was required to keep house in a dugout or cave, or, as the “cultured young lady of Chillicothe” might have put it, a hole in the ground.

The housing situation at the Meek farm could also explain why another young lady who responded to Arley’s invitation to call on him in 1916, after his divorce was final, never paid a return visit. Arley eventually took a homestead claim in Wiggins, Colorado, where he settled into the life of a solitary bachelor hunkered in a dugout. A relative who dropped by noted that, serving as hostess for the place, was the hand-carved wooden figure of a woman with marbles fitted into her lopsided eye sockets. Besides whittling human figures, Arley occupied his spare hours by making violins, smashing the ones that didn’t meet his standard of perfection. One suspects that the floor must have been fairly littered with splinters and strings.

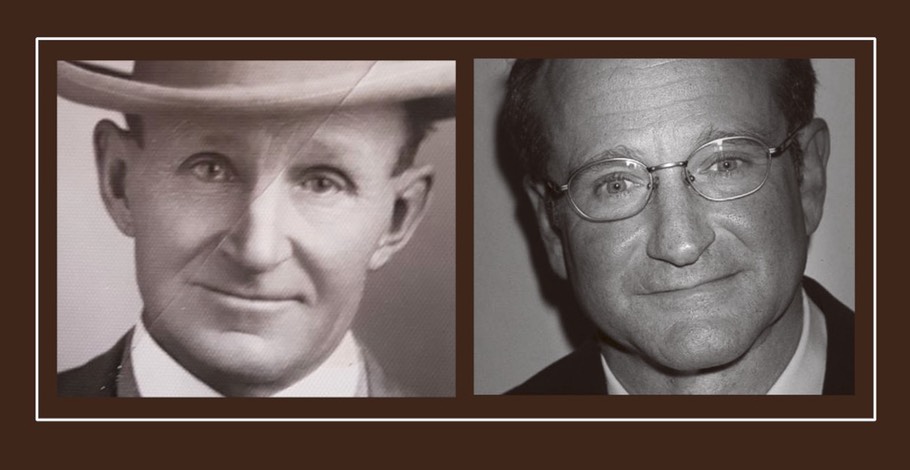

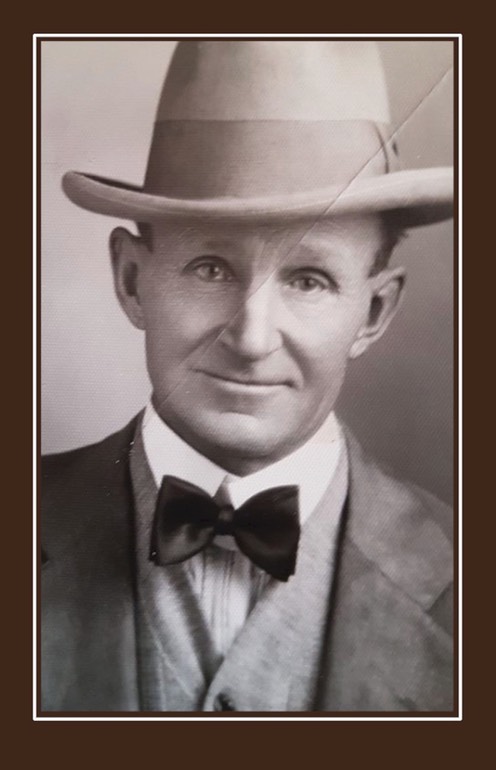

When I first wrote about Arley, I held out hope that he was the man in a picture of Wesleyan Business College students who resembles character actor Sterling Holloway (see A Series of Unfortunate Events), best remembered as the voice of Winnie the Pooh. Alas, that’s not him, judging from a handsome portrait Robert Meek provided, along with additional details about Arley’s life. Happily, however, a few people have pointed oute that the actual Arley was the spitting image of an even-better-known screen actor. No wonder everyone thought he was funny.