Phil Thornton, great-great-grandson of Thomas Lovewell and grandson of White Rock historian Orel Poole, hopes eventually to retrace Thomas’s trail across the West. He was already off to a good start, having grown up near Lovewell, Kansas, and moving to Illinois, where he now works for a corn maketing group.

When his job took him to Ohio last fall he made a day-trip to Nelsonville and snapped the pictures of the old family haunts displayed on these pages (see “Creepy Hollow”). The photo of a fully greened-out Round Mound, the natural landmark that let travelers know they were drawing close to White Rock, a sort of Pikes Peak on a miniature scale, was taken by Phil in the summer of 2014 and can be seen in the slideshow on this site. A recent trip to Washington, D. C. gave him the chance to visit the National Archives and examine Indian Depredation Claim files. When Phil’s schedule finally included Denver, he could hardly resist making a visit to Daniels Park.

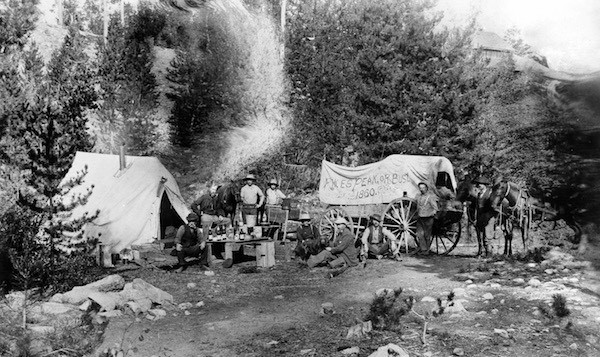

As I’ve made abundantly clear by now, I believe that Thomas Lovewell’s arrival at the Pikes Peak gold fields may have been captured by a pioneer photographer in the fall of 1859. I’m also certain that two of the figures on the left side of the picture are Denver’s early promoters, Daniel Chessman Oakes and Abram “California Abe” Walrod. When I first spied “Pikes Peak or Bust” in the online collection of the Denver Public Library in the fall of 2012, I had no idea where it was taken or what it represented, knowing only that one of its subjects looked unmistakably familiar. After connecting the dots, I realized that the names of all of the people in the photo might be deduced, as well as the setting, which almost has to be Riley’s Gulch where Oakes and Walrod pitched a tent beside a mill stream while the Oakes residence was under construction. The area is known today as Daniels Park.

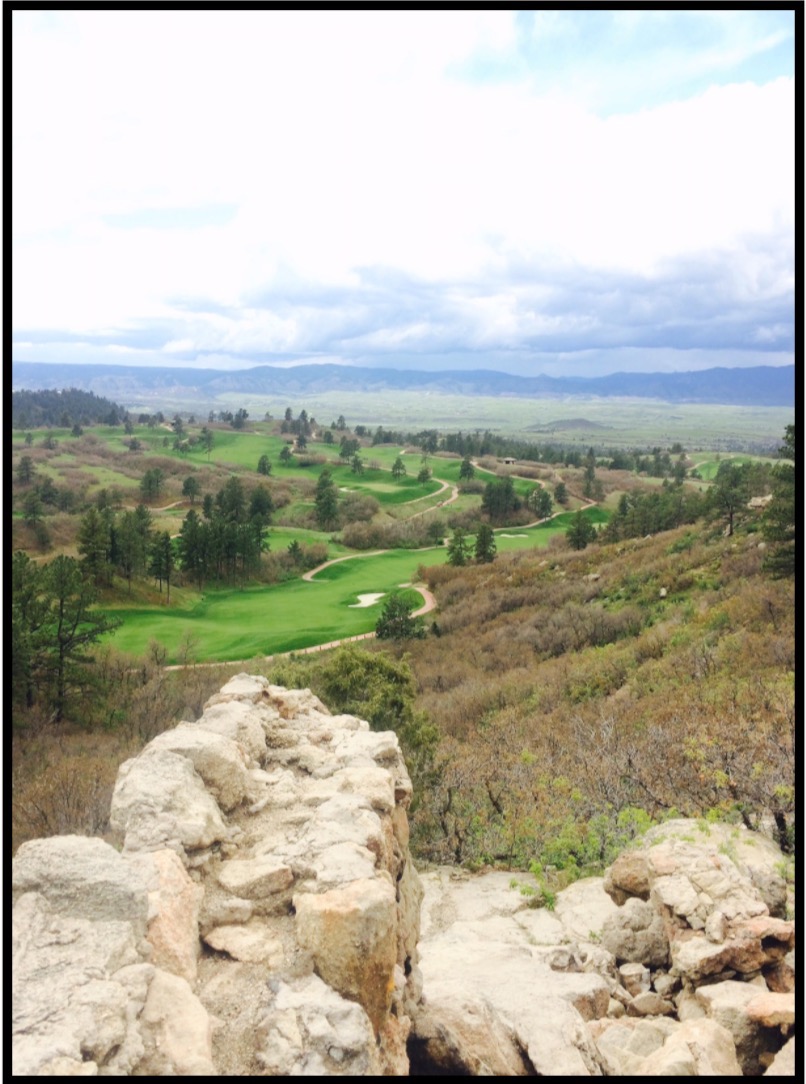

Daniels Park is a fenced-off thousand acre plot of land south of Denver, part of it devoted to Sanctuary Golf Course, another, home to a herd of bison. While Phil was not free to roam the grounds, stopping just off Daniels Park Road with what seemed to be the ruins of an old cistern at his feet, he photographed a view that struck him as something that could be the reverse-angle of the historic photograph. He was looking south, toward some distant foothills.

Phil pronounced the whole place “just beautiful. Had I been traveling west I would have stopped right there and made a home, back in the day.” Many travelers did just that. Daniel Oakes, author of a guide to the gold fields, may not have found a gilded payday himself, but he made a hefty sum providing lumber to new arrivals. His partner Abram Walrod made a fortune selling mining claims.

Thomas Lovewell resisted any temptation he may have felt to join the Denver crowd. After outfitting a wagon and setting out from St. Joseph, he probably had reached the Pikes Peak gold region after only the first two weeks of what would turn into a six-year sojourn, rambling from .

If he had stayed put in Denver, he would have missed seeing Pyramid Lake, Yosemite, San Francisco Bay, and Humboldt Bay, and would have met an entirely different cast of characters. Standing with his horse in what is perhaps now the rough of a fairway at Sanctuary Golf Course, Thomas Lovewell was only getting started.