The 1979 volume of family history The Lovewell Family has very little to say about Alfred Lovewell, and almost everything it does say about him turns out to be wrong. This is not the fault of the hardworking family researchers who handcrafted a valuable genealogical resource back when the Internet was a pipe dream. Any blame has to fall squarely on Alfred for leaving no progeny to keep his memory alive. However, as we’ll see, mistakes have long been a recurring theme in the tale a free-spirited young bachelor who was one of a pair of Lovewell brothers who died within the same month of the American Civil War.

What does The Lovewell Family Has to say regarding Alfred?

Tradition in the family says that Alfred had contracted Typhoid fever and was delirious. He is believed to have staggered from camp to the Mississippi River nearby, and wanting to cool off, had gone into the river and drowned, although his body was never found.

Ranked just after Thomas, whose name sits squarely in the middle of the stack among Moody B. Lovewell’s offspring in The Lovewell Family, Alfred turns out to have been the baby of the family, a 14-year-old living in his father’s house when the 1850 Illinois census was recorded. After Alfred’s death at Fort Churchill in Nevada Territory in 1863, his commanding officer copied the fallen soldier’s personal details from his enlistment papers, which described him as 5’ 10” tall with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. While transferring this information Captain Thomas E. Ketcham apparently misread the private’s age at enlistment, an error which would literally follow Alfred Lovewell to his grave.

Thus, on findagrave.com Alfred is said to have been 24 or 25 at the time of his death, an event which has somehow drifted upstream a whole year from its proper mooring on May 30, 1863. Alfred died eight days after his brother Christopher, who really did die at Vicksburg, not by drowning in the Mississippi, but cut down by enemy fire. Somehow, newspapers of the day managed to correctly print Alfred’s age at death as 27, while incorrectly calling him the first man in his company to die of disease. Perhaps they should have reported him to be the first to die of something weird, since his death was chalked up to “effects of eating poisonous greens.”

Ironically, Alfred was preceded in death by another private at Fort Churchill, Jeremiah Wagstaff, who also died of misadventure, drowning in the Carson River on May 1, 1863. It’s tempting to imagine that Thomas Lovewell’s reminiscence about the deaths of three soldiers he knew, falling within the same month of the War, somehow congealed in the mind of a young listener at his grandfather’s knee to become the story quoted near the top of this page. One soldier died at Vicksburg, one drowned in a river, and one was the little brother who died in the same fort where Thomas Lovewell served. In the mind of one grandchild, at least, all three became Alfred.

A few weeks ago I wrote about Alfred and a pair of accomplices breaking out of jail in Dubuque, Iowa, in the fall of 1856, before the three could be tried on multiple counts of “horse stealing and house breaking.” The version of the story I used also turned out to be inaccurate on a single point.

I thought at the time that Dubuque, a port city on the Mississippi River, was rather far removed from a crime spree in Monroe County, which is in southern Iowa, second tier north of the state line and a bit east of center. The story as published on November 5 in Burlington, Iowa, gives the Dubuque Republican as the source, saying that the trio of Alfred Lovewell, Thomas Robinson and William Stewart “were confined in the county prison of this place…” when the jailbreak occurred.

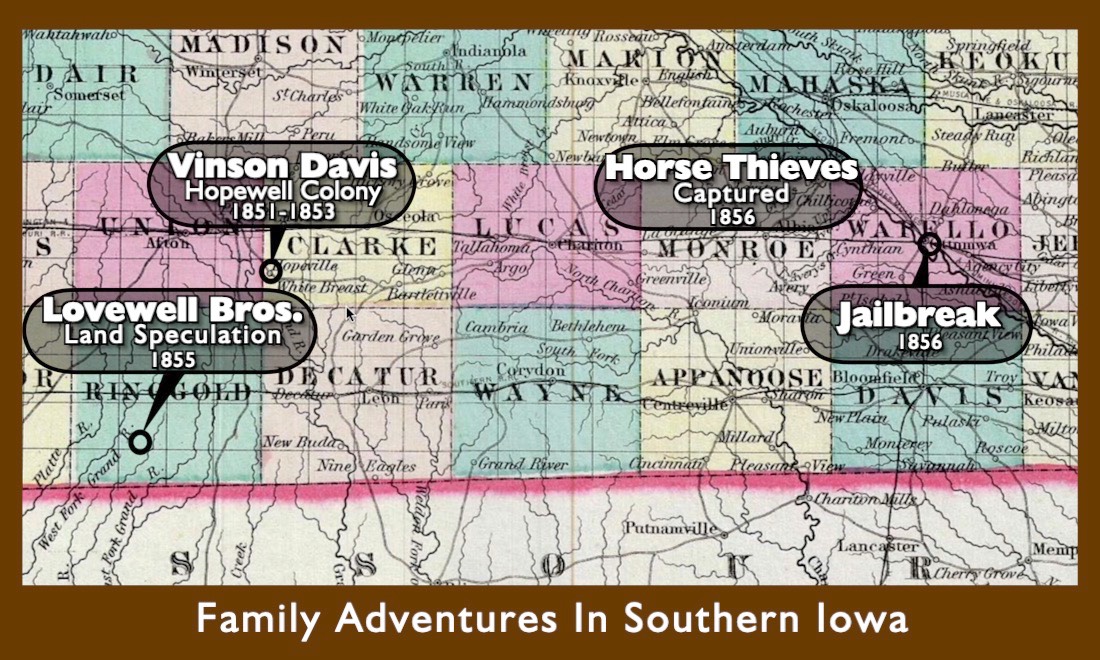

However, further searching revealed that the same paper had printed an almost identical item one week earlier, except for crediting the Ottumwa Courier for the story, putting the jailbreak in a totally different and much more logical part of the state, perhaps a mere twenty miles from the scene of the trio’s alleged crimes in Monroe County. The graphic above shows the site of the jailbreak in relation to the family’s previous activities in Iowa.

Although nothing further seems to have been written about the three escapees, the original story casts certain events in a different light, beginning with the 1857 census in Marshall County, Kansas.

The territorial census aimed to provide an accurate tally of bona fide residents who would vote for candidates with widely diverging opinions on the issue of slavery. Elections in 1854 and 1855 had been rife with fraud and bitterly contested. Marshall County apparently drew special attention for managing to produce an avalanche of votes for proslavery candidates despite being a settlement with no more than a handful of cabins.

We learn from a later census that Thomas Lovewell and his wife Nancy had come to Kansas in June of 1856, shortly after a proslavery mob from Missouri looted the abolitionist settlement of Lawrence.

In the 1857 census there is another Lovewell male listed in addition to Thomas, one with a somewhat indistinct first initial, which genealogist Mary Penner decided might be an “A.” Hats off to Mary because her identification now makes perfect sense. With a posse on his tail Alfred Lovewell suddenly needed a place to lie low, away from his usual haunts. His appearance in Kansas also may have influenced Thomas’s ambitious bids to bring regular mail service to Marshall County. The largest prize in the bidding war would have been the route between Marysville and the territorial capital at Lecompton three times a week for an annual fee of more than $4,000.

Eight years ago I speculated that if Thomas “had been awarded one or two of the big prizes he would have needed to buy or rent wagons and a stable of horses and hire employees. Perhaps he thought of the new business as a way to lure his brothers to Kansas as partners or members of his crews.”

It turns out that one brother was already there by 1857, a brother who knew a couple of guys who could get all the horses they would need.

As I wrote in “A Trail of Golden Crumbs,” the story of Alfred’s jailbreak may also help explain a rumor passed along by pension investigators in Iowa in the 1920’s that Thomas Lovewell was once thought to be engaged “in the horse-stealing business on a very extensive scale.” He may have been, but perhaps old-timers were recalling another young Iowan named “Lovewell.”

It would fit right in with Alfred’s story if they had blamed the wrong man.