I’ve sometimes compared researching family and regional history to waking up at night in a strange house in an unknown land and trying to describe the outside world by pressing an eye against a shuttered window and peering through the slats. That’s what it can feel like, trying to piece together a vision of the past out of census returns, land files, and newspaper clippings.

Successive census forms do allow us to accumulate various odd little bits information. The 1940 census asked respondents what level of education they had attained. The 1850 census contains land valuation and personal worth. We learn, for instance, how many head and what kind of livestock Thomas Lovewell owned. The census often recorded whether a listed family member was able to read or write. Learning that Moody Bedel Lovewell, Jr., could do neither, coupled with the fact that, after his father’s death he became part of his younger sister’s household, enables us to make certain guesses about him.

After so much squinting in the dark, along come photographs like those shared recently by Norm Stofer’s family, which illuminate the landscape with sudden flashes of lightning. In a note thanking Norm’s daughter Dale for sending me copies of those pictures, I started to state my old “strange house in an unknown land” metaphor in reverse, putting us outside peering in through the shutters, before deciding that the wording made family researchers sound like a bunch of Peeping Toms. So I switched it around. On the other hand, occasionally, I do feel like an intruding snoop.

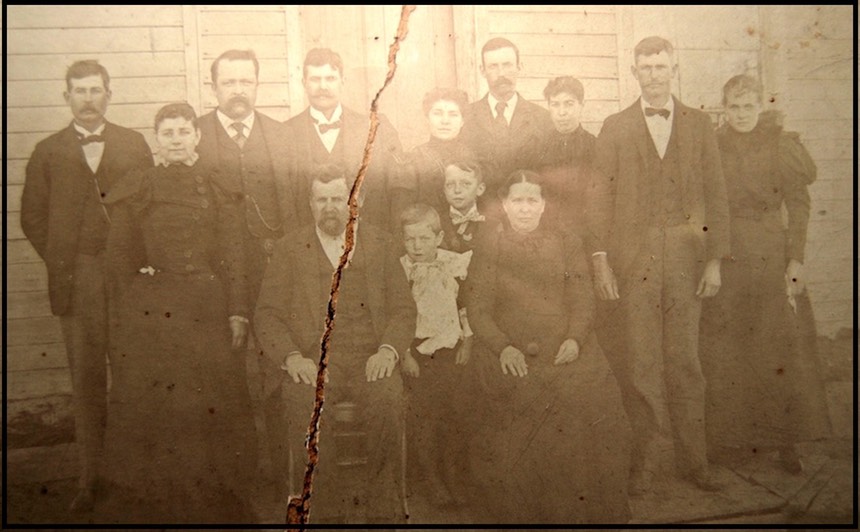

Recently, as I was trying to perform digital repair on a torn photo (shown unretouched on the left) of that somber-looking group gathered on Jacob Stofer’s porch circa 1898, I found myself gazing uncomfortably at a scene of raw grief.

Given the circumstances, it now seems to be an accusing stare on the tear-streaked face of Mary (Lovewell) Stofer as she tries to conceal the handkerchief wadded in her left hand. The man at her side, her husband Ben, glares back at us like a feisty John L. Sullivan looking for an opponent to clobber.

Having had some time to think about it, there are probably as many good reasons to suppose that the grief was for Mary’s second child as for her first. The two infants died only a year apart, Mabel at two weeks of age, Jessie Lloyd at three months. Given the fact that only ten months separated their births, it seems likely that Jessie Lloyd was born prematurely and clung tenaciously to life for as long as he could.

An odd thing about the photo is that, as you can see, it’s been torn in two, perhaps accidentally, yet in just the right spot so that not one face was transected. The worst that happened was the loss of part of an ear by Jacob Stofer. Whether someone started to rip up the photo and then thought better of it, the picture reminds us that death was a frequent visitor in those days, and apparently a good excuse for a group photograph. It’s sometimes estimated that 40% of children in 19th century America did not survive to adulthood, making Ben and Mary Stofer’s experience, however tragic, exactly average.

Census information does sometimes provide details that photographs simply can’t, and vice-versa. Once in a great while they collude, and one simply illustrates the other.

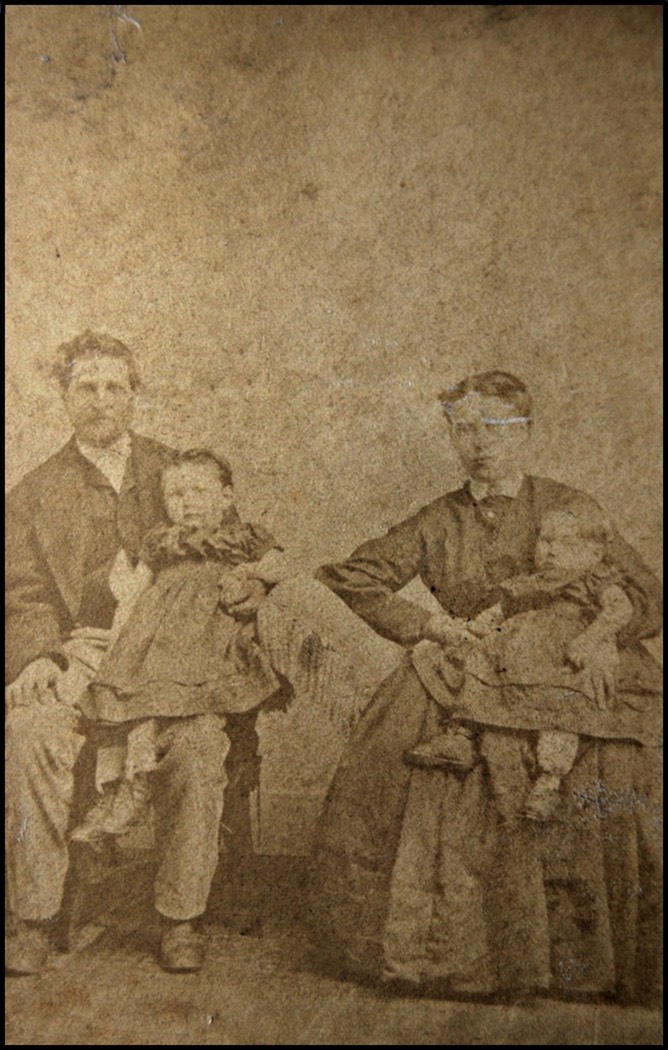

That happened with what seems to be a copy of a particularly muddy ferrotype of Jacob and Nancy Stofer showing off their growing family in Muscatine, Iowa, in 1870, seven years and several children before their arrival in Jewell County, Kansas. A census return from that year could serve as a caption for the photo, while providing the additonal information that Jacob had earned the family’s nest egg of $800 by working as a peddler (written with the word’s original spelling, “pedlar”). Jacob’s age is given as 25, while Nancy is 20, and their children Mary and Bursy are not quite 3 and just over a year old, respectively. The census may have been taken just a few months after the photograph.

I’ve tried to be consistent in calling their eldest son “Bursy,” which is how his name appears in many sources. In his first appearance in the 1870 census, however, it seems to be rendered as “Burr,” perhaps an indication that “Bursy” was a diminutive form, a childhood nickname that stuck with him for the rest of his life. Here and there he’s called “Burzy,” “Burgy,” and “Burj,” as though no one was completely sure what his given name really was. I’ve allowed the inscription on the gentleman’s headstone to have the final say on the matter.

What’s certain is that Jacob Stofer and his family embraced photography from the very beginning, and in all of its diverse forms, highly-retouched and tinted formal portraits, photo-postcards, tintypes, even the noisy and indistinct ferrotype above, which may be clearer than the word-picture drawn by the census, but not by much. Whenever tragedy brought the family together and demanded that everyone assemble in their Sunday best, a cameraman was sure to step forward to capture the moment.

The affinity for photography was contagious, or perhaps congenital. As we’ve seen, the first home snapshots of the Lovewell family were apparently taken by Ben and Mary Stofer with a Kodak Brownie early in the 20th century. Ben and Mary’s own life together, like that of Ben’s parents, would be fully documented in pictures. Sharp, clear ones.