As certain recent events unfolded, something kept tugging at my sleeve. What was it about all of this that seemed so oddly familiar? It took some time to figure it out. Time, and a bit of unrelated digging.

An unarmed young man lay dead in the street, the tragic victim of trigger-happy policing, according to some witnesses. A law officer drew his weapon and shot a man who had raised his hands in a gesture of surrender. Others who were passing on the street that day or looking out their windows, believed they had witnessed a justified police shooting. Both sides shared their version of events with news outlets, and battle lines were drawn. Friends of the deceased took to the streets in protest, and cried out for justice. After days of contradictory testimony, a grand jury refused to return a bill of indictment in the case. What many saw as a miscarriage of justice led to smoldering resentment and further outbursts of violence.

The historic connection didn’t occur to me until I began leafing through Territorial Nevada newspapers, of which there are still only a pitiful handful available online. Knowing that Thomas Lovewell was in the Comstock region early in 1864, I went looking for some mention that a letter had arrived for him and was waiting at the Dayton Post Office, or that he had taken lodgings in a local hotel and was ready to receive old friends wishing to pay a call. It was a long shot. Lacking any newspapers from that era for Dayton, I had to settle for issues of the Virginia Evening Bulletin, published at Virginia City, eight miles to the north, but a town where Thomas Lovewell had shared a miner’s shack four years earlier.

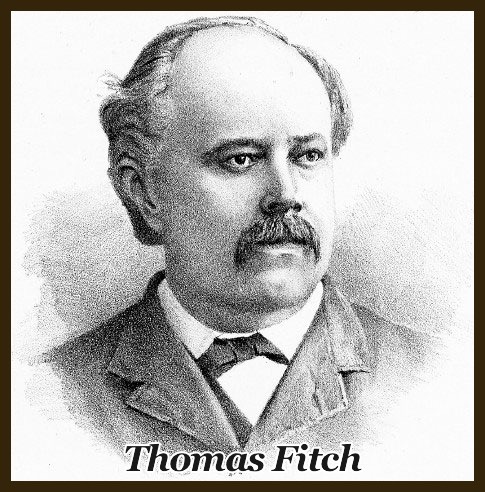

What caught my attention in the yellowed pages from 1864 Virginia City was an advertisement for a local attorney named Thomas Fitch. Fitch would make a name for himself as a skilled orator and politician, as well as a writer, newspaper editor, and associate of the young Samuel Clemens who was just beginning to attach the byline Mark Twain to his work. It seems fair to call Fitch the Alan Dershowitz of his day. He sometimes took high-profile clients and did not shy away from controversy, defending Brigham Young and other Mormon leaders when they were prosecuted for polygamy, and serving as general counsel for the Church. However, today Thomas Fitch is surely best remembered as the lawyer who defended the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday in the killing of Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury, and Frank’s brother, the unarmed Tom McLaury, on a vacant lot in Tombstone on October 26, 1881.

The brief blaze of gunfire that day is commonly referred to as "The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral," a misnomer, since the fight did not occur there or even in an adjacent area. The name probably did not attach itself to the story by accident or because it has thrilling ring to it. Where did it come from? One Western writer has suggested that it was shrewdly coined by the prosecution team to plant a suggestion that the slain were preparing to leave town peacefully, when the Earps confronted them with pistols at the ready, and Doc Holliday leveled his shotgun. After the bullets stopped flying, calling what had just happened “The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” was the first volley in a war of words.

There is no real similarity between the shootings in 1881 Tombstone and a recent one in eastern Missouri. According to Earp specialists Casey Tefertiller and Jeff Morey, Wyatt Earp did not draw his pistol until he saw Frank McLaury go for his, and while Tom McLaury wore no sidearm, there was a rifle in a nearby saddle scabbard, and he appeared to be reaching for it when the horse bolted, allowing Holliday to pump a load of pellets into McLaury. Two of the policemen in the case, Virgil and Morgan Earp, were wounded in the gun battle, and Doc Holliday was grazed by a bullet. In short, this was no one-sided gunfight.

Where 1881 and today start to mirror each other is in the media battle that ensued. There is a familiar pattern to what we see these days after a controversial shooting - public figures, politicians and pundits are trotted out in front of cameras and microphones to give events their patented and predictable slant, competing cable news networks send facts spinning in opposite directions, and there are sure to be selective leaks of damning evidence.

There were no TV cameras or microphones in 1881, but an effective PR process was firmly in place on both sides. The dead were immediately propped up in their silver-trimmed caskets in the undertaker's window with a placard reading “MURDERED IN THE STREETS OF TOMBSTONE.” Conveyed to their graves in glass-lined hearses followed by an entourage of 300 mourners, the dead were laid to rest as if they had been citizens of note. Far from being upstanding residents themselves, the Earps were now rumored to be part of a notorious gang of stagecoach robbers, at least, according to Ike Clanton’s testimony and a whispering campaign.

For his part, Thomas Fitch made sure Wyatt Earp testified by reading from a prepared statement. Fitch’s grueling cross-examination of prosecution witnesses rattled some of them, leading to contradictions, and making them look like buffoons. He also tried to get Cowboys to admit on the stand that they were known by aliases and were desperate, wanted men hiding from justice. It didn’t matter whether any of these allegations were supported by evidence. What was important was that seeds of doubt were sown.

The Clantons and McLaurys were suspected of being part of a loose confederation of outlaws known as the Cowboys, who supported one another with firepower and alibis whenever needed. While not tightly organized, the Cowboys did have their own media outlet, the Tombstone Nugget. Perhaps because the publisher was out of town that day, directly after the shooting the Nugget ran an evenhanded account of the Tombstone shooting, one which was remarkably similar to Wyatt Earp’s later testimony. That would all change in the coming days, when publisher Harry Woods returned to town and the newspaper began to toe the party line.

According to their witnesses, the Clantons and McLaurys were standing with their hands in the air when the Earps and Holliday confronted them. Hadn’t Tom McLaury even opened his vest to show that he was unarmed? When the lawmen started shooting them down, the Cowboys had no choice but to return fire. Judge Wells Spicer did not buy the Cowboys' story and neither did a grand jury.

Although the Earps and Holliday would not face trial, this was not nearly the end of the bloodletting in Arizona, and may not have been the end of the media blitz, either. There is no evidence that Thomas Fitch or another Earp supporter had anything to do with planting it, but a news item appeared after the verdict, and in the 19th century version of going viral, it was reprinted in a number newspapers.

The unnamed writer, said to be a Texas correspondent for the Philadelphia Bulletin who visited New Mexico Territory in 1881, penned a derogatory article which ran under the headline “Characteristics of the Cowboy.” He called the Cowboy “a peculiar product of the frontier; as a rule, it is base flattery to suppose that he ever drives cows, unless he steals them … With him the revolver is a substitute for all things; he argues with it most logically, he buys with it at his own price, and he amuses himself with it habitually.”

The correspondent provided several examples of Cowboy antics, including one about a church in Charleston, Arizona, where a minister was forced to dance a jig at gunpoint, a variation of a prank usually attributed to Ike Clanton and Cowboy chieftain Curly Bill Brocius. The writer also suggested that the only antidote to the Cowboy problem was extermination, an undertaking that was apparently underway.

Two or three days after we left Deming one of them, in a half inebriated condition that is chronic with his class, attempted to ‘run’ the town. He rode through the depot on horseback, brandishing his pistol and scattering the bystanders promiscuously; one of them, not getting out of his way promptly, was knocked down by a blow from the outlaw’s pistol.

A deputy sheriff, armed with a shotgun appeared on the scene and ordered the cowboy to surrender. He failed to comply, when the deputy shot him dead. Three were killed at Tombstone the other day in a conflict with a deputy marshal and his aids, who had arrested one of their number a short time previously. A frontier jury doesn’t hesitate very long over a verdict of ‘justifiable homicide’ when a cowboy is killed.

Considering everything that happened next, if Tombstone's Cowboys ever read the item, they may have considered these fighting words.