Several years ago the TV game show “Jeopardy" featured a category all about Davy Crockett. One of the answers went something like this: When he was campaigning for reelection, Congressman Crockett once ordered a hundred of these, fearing that he might run out. None of the players could offer the correct question, What is a coonskin cap? In fact, no one scored a point in the entire Crockett category. I’m not sure anyone even felt knowledgable enough to buzz in. Alex Trebek responded to the baffled stares from the three contestants by improvising a new refrain for the old Davy Crockett ballad:

Davy, Davy Crocket - we don’t remember you!

It was around that time, while leafing through a volume in a mall bookshop, I discovered that it was open season on Davy Crockett’s coonskin cap. I was looking at one of those books designed to teach the reader, in breathless prose, that he knows less than nothing about history.

Did you know that David Crockett served two terms in Congress? And he did not wear buckskins in Washington, but the ordinary street clothes of his day. And there is no evidence that he ever wore a coonskin cap.

Anyway, that’s the gist of what I remember reading. I wasn’t sure about the coonskin cap, but I did know that the Honorable David Crockett of Tennessee did not serve two terms in Congress. He served three. So, could this guy really be trusted to get the business about the cap right?

Not long afterword, I read a Smithsonian article written by Eric von Schmidt, an artist who had just painted his masterpiece, “The Storming of the Alamo.” Schmidt proudly recalled that he had avoided painting Davy Crockett in a coonskin cap, in order to make the painting historically authentic. Yes, he admitted, Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson did say that when she was led from the chapel into the open air, she saw Crockett’s body "and even remember seeing his peculiar cap lying by his side.” The artist was quick to deal with Mrs. Dickinson’s recollection by defining two key words in her testimony.

At the time the word ‘cap' only implied headgear with a visor, and ‘peculiar' in this instance, didn’t mean odd. It merely meant the cap was Crockett’s particular hat. And since in my view he didn’t wear coonskin hats generally, I did not take the large leap into mythology required to equate ‘peculiar' with ‘coonskin.'

Hmm. All caps had visors in those days, did they? Interesting. You mean, as in watch caps, nightcaps, skull caps, caps & gowns, and, oh, I don’t know … coonskin caps? All of these caps have gotten along quite nicely for some time now without visors. As for Mrs. Dickinson’s use of the word “peculiar,” doesn’t it make more sense to suppose that she used the word with another meaning it could convey, even in the 1800’s, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, that of singular, uncommon, out-of-the-way, strange. Otherwise Mrs. Dickinson would merely be saying, his hat that was his hat. I find it much more likely that she meant to say she saw his hat, the one that could be no one else’s. Schmidt balked at taking the leap from “peculiar” to “coonskin,” but eagerly took an even larger one, painting David Crockett wearing something like the wheel cap we associate with U.S. troops during the Mexican War, an item no one ever reported seeing on his head. Now that’s peculiar.

Three years ago the situation became even more ironically muddled, coonskin-wise, when Jeopardy champion Ken Jennings decided to wade into the ring to debunk what he called a “1950’s Myth” which by this time had already been beaten black and blue. Jennings was circumspect in his claim, defining as “myth” only the idea that Crockett had worn a coonskin cap during his frontier days, though he too challenged the cap’s appearance in the frontiersman’s final battle in Texas.

According to Jennings:

There are at least three eyewitness accounts of Crockett wearing a coonskin cap on his fateful final journey to the Alamo, but all were recorded decades later, when the legend of a coonskin-wearing Davy was already deeply embedded in myth. One comes from Crockett’s youngest daughter, who also misremembers the rifle her father took with him on the trip, so her account is particularly suspect.

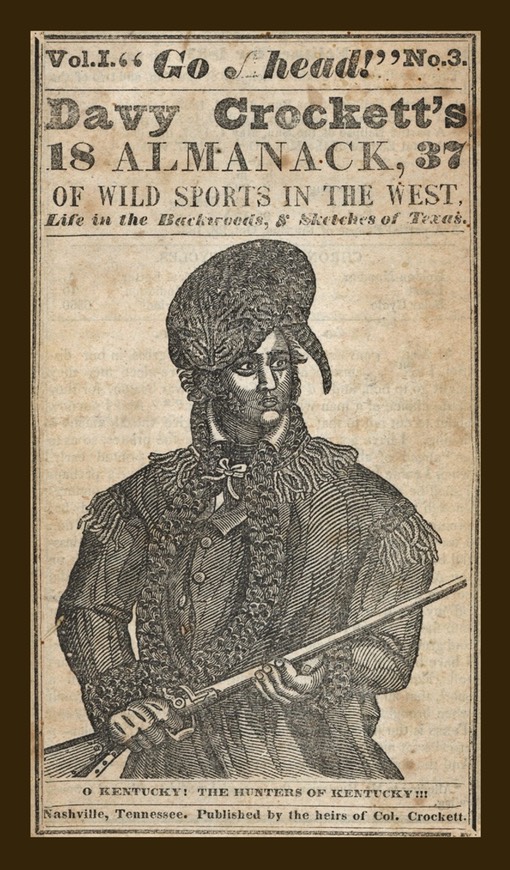

I had to press the rewind button on that paragraph to make sure I read it right. Let’s see, in addition to Mrs. Dickinson’s memory of seeing Crockett’s “peculiar cap” after his death, there were three eyewitnesses, including his daughter, who saw him en route to the Alamo wearing a coonskin cap - but all of them must have been victims of mass hypnosis, because … well, because we debunkers just know better. Jennings speculates that Crockett’s fur cap may have had its origins in the play “The Lion of the West,” which was unmistakably based on Crockett’s career. The Congressman himself attended a performance of it in 1831, acknowledging a bow from the star player with a bow of his own. The lead character, a backwoodsman named Nimrod Wildfire, strode center stage clad in fringed buckskins and crowned with a cap that appeared to be fashioned from the skin of a bobcat. The cover of an 1837 Crockett Almanac, supposedly a portrait of Crockett, is actually an illustration from the playbill from “The Lion of the West.” But why would this fictionalized version of Crockett have worn furry headgear, unless it was what audiences expected to see?

There’s also the matter of “Colonel Crockett’s Exploits and Adventures In Texas,” a narrative long attributed to David Crockett but actually written by Richard Penn Smith and rushed into print soon after the Alamo fell. In it, one of Crockett’s ghost-written diary entries tells of putting on “a new fox skin cap with the tail hanging behind,” before setting out for Texas. Perhaps coincidentally, one of Santa Anna’s men, Sergeant Felix Nuñez, many years afterward would recall seeing a tall American "who had a long buckskin coat and a round cap without any bill made of fox-skin with its long tail hanging down his back.” Yes, Nuñez was by then an old man, but Richard Penn Smith scribbled his potboiler while Crockett’s ashes were still warm.

There’s nothing here of earth-shattering importance, unless there's some conspiracy in the works against the coonskin-cap industry. The case does illustrate the delicate process that goes into assembling history out of little bits and pieces of fact, memory, and supposition, and a lot of glue. Sometimes the pieces have to be hammered and whittled, and sometimes the assembled puzzle doesn’t quite resemble the artist’s rendition on the cover of the box. Often, there is no real consensus, just a lot of noisy opinions.

For instance, many people find compelling evidence that David Crockett was one of a handful of defenders who were captured and executed after the fall of the Alamo. Others insist that he died fighting, gamely swinging his rifle like a club when there was no time to reload.

I don’t care either way, but I’m willing to bet that, however he died, he went down with some sort of critter on his head.