An aged Civil War veteran, stooped and grizzled, showed up in Mankato, Kansas, on November 4, 1891 to convince a panel of examiners that he qualified for what was called an invalid pension.

I have rheumatism all over me. My hands hurt me all the time. If I exercise much I cramp so I can’t sleep at night. I have pain frequently around my heart. My knees pain when walking. Was discharged for Rheumatism.

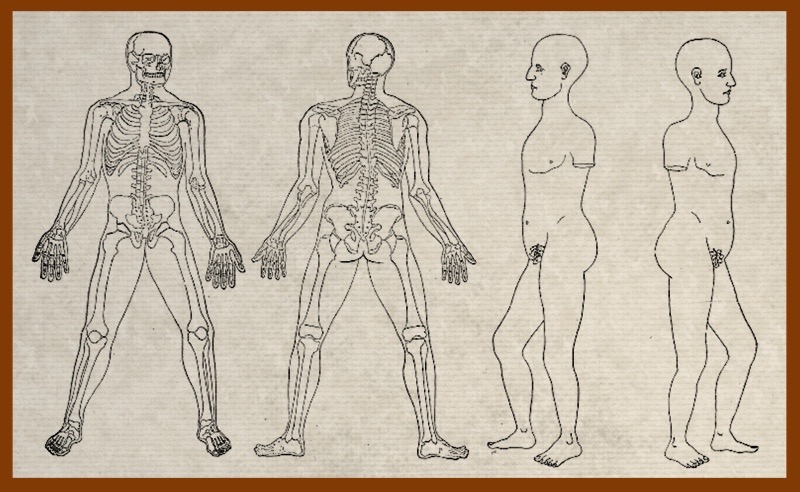

The patient listed his complaints while a doctor looked him over and jotted down his own observations, using arcane and sometimes indecipherable medical jargon. The form he used was supplied with line drawings of a human figure where the doctor could have marked the location of a patient’s wound, if there had been one.

He noted the presence of rheumatisive joints on fingers of both hands, and found muscles on the old man’s hands were atrophied. Veins were enlarged. His knees appeared swollen and the ligaments had become shortened or lanceolated, restricting motion of the knees by half. Except for these ailments and a varicose vein on his left leg, the soldier otherwise seemed in remarkably good shape for a man of his age. Heart action was normal. Pulse rate was 72, respiration 22, temperature 98.5, height 5 feet 10 ½ inches, weight 158, age 66 years.

The Dependent Pension Act of 1890 no longer required the cause of a veteran’s disability to be related to his military service, but the old soldier may not have been aware of this latest wrinkle. He cited rheumatism as the cause of his current disability, naming it also as the reason for his early discharge from the 3rd California Volunteers back in 1864. According to his service record he had instead been released because of phthisis, a condition of the lungs with a name the old man may have forgotten, or perhaps couldn’t pronounce. If the examiner noticed the discrepancy, he was too polite to point it out.

1888, the last year when such a tabulation was made under the old rules, more than 47,000 Union veterans applied for disability benefits. Fewer than five percent of these were granted. At the Bureau of Pensions in Washington, D.C., in February 1892, the application made on behalf of Thomas Lovewell sailed past both a legal reviewer and a medical referee, who recommended that he receive $12 a month, paid retroactively from September 4, 1891. The government’s purse strings had been loosened lately by the new Act of 1890, thanks to relentless campaigning by the G.A.R. and a national election that may have turned on President Grover Cleveland’s veto of the Dependent Pension Bill of 1887.

Pensions had become a hotly-debated topic, and paying them took a significant chunk of the federal budget. The War with Mexico in 1846 had involved only about 100,000 American soldiers, yet it was not until 1887 that the country got around to doing something about service pensions for veterans of a war that gained it most of its New Southwest. In 1889, approximately 8,000 claims were allowed for the surviving men who had served in it. However, nearly three million men had joined the Union Army during the American Civil War. While providing service pensions for many of them would prove quite costly, ignoring this huge voting bloc amounted to political suicide. Congress decided to pay up.

Eventually, old age alone would be considered proof of disability. Anyone 62 or older could start receiving benefits from his service many years earlier in the fight to preserve the Union and end slavery. The $12 a month Thomas Lovewell began drawing at the age of 66, should have seemed like a bargain.

Stepping out of the examination room, Lovewell probably straightened up to something closer to his former height of six feet, and walked with a suddenly brisk gait to the train depot. The exam had gone well. The doctors seemed sympathetic to his debilitated condition. If he received it, the extra money would come in handy for a prospecting trip to Wyoming he planned to make next summer. There would be seven of those in his future, as well as a year spent exploring wild Alaska, along with a few other trips to drop in on relatives here and there. It was hell being old. It cut down on a man’s ability to travel.

A record of Thomas Lovewell’s examination for an invalid pension has been added to the photo page.