I’ll admit that I started looking into the life of Silas Stillman Soule only because of his looks. In the first picture I ever saw of him, he looks enough like Thomas Lovewell that he might have been a long-lost younger brother. Soule had the same fiercely expressive eyes, a smartly-trimmed mustache and thick head of hair, determined jaw and prominent cheekbones.

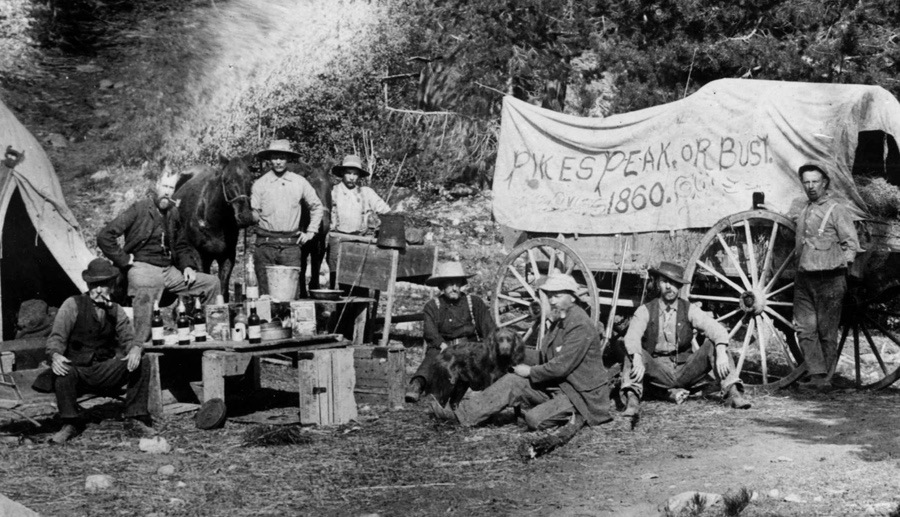

I came across the picture of Soule in a book about Daniel Chessman Oakes, the man I believe to be the figure whose marred image appears on the left-hand side of the “Pikes Peak or Bust” photograph posted on this and many other websites. According to the Oakes book, Soule went to Pikes Peak in May of 1860 and lived for a time in Denver, leading me to wonder if I could be dead wrong about the identity of the man standing to the right of Oakes: Could it be Silas Soule instead of Thomas Lovewell who is holding his horse’s bridle with one hand while, assuming a pose of youthful confidence by resting the other hand on his hip?

As I’ve mentioned many times before, I've handed out tentative I.D. tags to several men in the picture. In most cases there are multiple threads of evidence leading me to believe that we can figure out who each man is. The one who resembles D. C. Oakes (After we mentally reconstruct his cranium) and has the style of beard and the single curly strand of hair seen in a famous photograph of Oakes, also seems to be living in a tent beside a mill stream located in a gulch near Denver, just as Oakes did. The seated man wearing an oversized white cowboy hat, resembles a younger version of John Henry Williams, an immigrant from Cornwall whose only other readily available photographs show him enjoying his golden years, sporting a white goatee. However, there’s more to the identification than facial similarity, since Williams’ grandson is the patron who donated the historic Pikes Peak photo to the Denver Public Library, lending credence to the idea that one of his ancestors might be depicted in it. Why else would the family have kept as an heirloom? Besides the fact that Lovewell said he was there around the time the picture was taken, my main reason for believing that a traveler posing beside his horse could be Thomas Lovewell, is that he looks like him. Exactly like him in every detail. So, the idea that a doppelgänger also might have been on the scene in 1860, got my attention.

Although Silas Soule was thirteen years younger than Thomas Lovewell, the two had followed some of the same paths. Silas was born in Maine to abolitionist parents who brought him to “Bleeding Kansas” in the 1850’s, where the Soules lived at the settlement of Coal Creek near Lawrence. A friend of John Brown, Silas was active in the Underground Railroad, and was one of the men who sprang Dr. John Doy from a Missouri jail, after Doy was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary for trying to lead a group of slaves to freedom. Soule and his fellow Jayhawkers brought Dr. Doy to Lawrence in triumph and had their pictures taken with him, dubbing themselves, “The Immortal Ten.” After John Brown was captured at Harper’s Ferry, Silas Soule traveled to Virginia with plans for another jailbreak. However, Brown insisted on martyrdom, believing his death would ignite the coming revolution against slavery.

Soule joined a flood of prospectors headed to Pikes Peak in 1860, enrolled in a regiment of Colorado infantry in 1861, and helped fend off a Confederate invasion at Glorieta Pass, New Mexico Territory, in 1862. His commanding officer, Maj. John Chivington, was so impressed by Soule that he promoted the young lieutenant to captain. The two were both fire-breathing abolitionists and seemed to get along well. When his term of service was up, Soule enlisted in Company “D” of the First Regiment of Colorado Cavalry, an outfit commanded by Col. Chivington that would secure a place in Western infamy with the Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864.

After a march through a frigid Colorado landscape and a night of revelry in anticipation of the coming battle, men of the First and Third Cavalry appeared at dawn near the edge of the Sand Creek Reservation where Chief Black Kettle’s bands of Southern Cheyennes and Arapahoes were encamped. Col. Chivington deployed his troops and gave the order to charge. Seeing old men scrambling out of their tipis carrying white flags and the Stars and Stripes, Capt. Soule refused to order his company to join the attack. Instead, he watched the Colorado Cavalry begin a rampage of one-sided sadistic butchery, before he frantically rushed into the village to shield as many innocents as he could.

Crowds in Denver greeted the victors with cheers as Chivington’s troopers showed them bloody trophies of the carnage, waving Cheyenne scalps and other body parts. While Chivington had Soule and a few other militiamen arrested and charged with cowardice for refusing to join in the bloodbath, when word got out about what had really happened at Sand Creek, public opinion began to turn. Eventually, Soule testified against Chivington at his court-martial. Eighty days after giving his testimony, twenty-six days after his wedding to Hersa Coberly, Silas Stillman Soule was assassinated while investigating a report of gunplay near his home. He was twenty-six years old, and had spent his short life always firmly determined to do the right thing.

It seems almost beside the point to report that Soule is not the man in the Pikes Peak photo. He still looked like a boy in 1860, with not a line on his face and a jaw that seemed padded with baby fat. His war experience aged him somewhat, and the mustache may have been a late experiment to make him look more mature. Judging from the photograph of “The Immortal Ten” standing around Dr. Doy at Lawrence, Soule was a man of no more than medium height, if that. His father Amasa Soule was described as “not too tall.” One thing Silas did have in common with six-footer Thomas Lovewell was a wedding date. If Silas Soule had lived to celebrate his anniversary, both men would have been expected to remember the significance of April 1st, besides its being April Fool’s Day.

Another similarity the two men shared is a widow’s pension case file that could be sold by the pound. As I investigated Capt. Soule’s military record I discovered that what should have been an open-and-shut pension case, ran to 232 pages of material and contained a few surprises. But they’ll have to wait for another time.