Taking photographs has become so effortless and thus so commonplace that almost any whim becomes a photo opportunity. Check out the number of cat pictures on your own phone to see what I mean. In the era discussed on this site, photographs were usually triggered by comparatively seismic occurrences - long-awaited homecomings, the birthday celebration of an aged family patriarch, or what was certain to be an extended family’s last Christmas together.

Understanding why a picture was taken can give it new layers of meaning. For instance, a photo of Ben Stofer apparently driving his family down the streets of Lovewell initially struck me as a posed event because there’s no motion-blur on the spokes of the wheels. The car is obviously standing still and Ben is only pretending to steer it with an air of manly determination. Learning that Ben’s brother-in-law was automobile salesman Arizona J. White, suggests that the picture may have been snapped as a marketing tool for his dealership in Belleville. Perhaps a copy of it joined several others pinned to a cork board in Arizona’s Chevrolet showroom.

A few years ago I called attention to an item in a 1913 issue of the Lovewell Index which reported that Ben Stofer had driven Mrs. Ed Davidson to Mankato in his new car, when she began babbling alarming nonsense following an apparent case of sunstroke.

Was his new car the same one we see in this photo? If so, then the picture had to have been taken in 1913, and Ben can be seen sitting behind the wheel of a rare and very early model of Chevrolet, before the radiators began sporting those elegant bowtie trademarks. A close inspection of the picture reveals no discernible emblem, (although I’m told that it didn’t appear on all Chevy models before 1915). I also can’t help wondering - if Arizona White happened to be prowling the streets of Lovewell one fine spring day in 1913 with an excellent camera tucked under his arm, his presence in town that day could be the reason we have a crisp closeup of Mary Stofer’s mother, Orel Jane Lovewell, who may have been coaxed into standing still for a moment as she walked uptown to the post office to fetch her mail.

The pictures and news clippings provided lately by Stofer descendants are like a giant box of puzzle pieces almost begging to be fitted together, or else matched with older pieces already lying scattered about my computer desk. I remember reading a brief news item from the Lovewell Index - I believe it was a 1914 issue - when Thomas Lovewell’s son Simpson Grant announced that he was headed off to spend the entire next year touring the Far West. While he seemed to turn up in the Lovewell area far ahead of schedule and without fanfare or any explanation from the Index, there is a tiny, yellowed newspaper clipping in the Stofer scrapbook, possibly lifted from the Hardy, Nebraska, Herald, announcing: “G. S. Lovewell has returned from the gold field. He says it is no place for a poor man.” Despite reversing the subject’s initials, the paper's quote from him sounds genuine.

There’s a much longer account from the Hardy Herald in the Stofer treasure chest, one written by Ethyle Dahl and evidently printed in 1948, detailing a road trip taken by Ethyle, her husband Martin and their son Dwayne west of Kearney on Highway 30, bound for Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon and Washington. Aware that they were following the route taken by earlier generations, Ethyle wrote,

The courage of the pioneer kept coming to mind. They broke this trail where the Union Pacific and highways go west. My grandfather Lovewell went the same way in 1849 as a scout for the wagon trains. They had strength and fortitude with a vision. Do we rate as well in 1949?

Although I remain an agnostic about Thomas Lovewell’s journey west so early in his career, I can understand the urge to follow his trail and see the sights he saw, no matter what year it was that he first laid eyes on them.

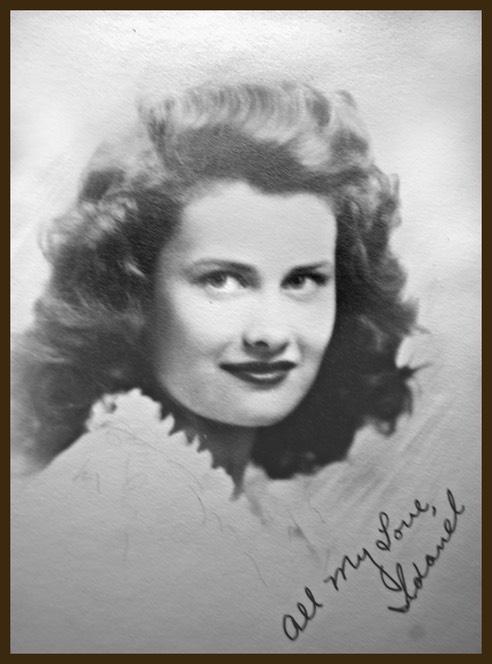

Some of the items shared by Ashley Gresham concern the Williams side of her family, including her grandmother Idanel, the daughter of Isaac Milton Williams and his wife Nettie (Megaffin). Idanel married Ben and Mary Stofer’s grandson Norman, Bennie Stofer’s boy. When I saw the picture Ashley provided of Idanel, my first thought was that it looked like the sort of wallet-sized photo that used to come with the wallet. They were always pictures of improbably beautiful people. My first billfold contained small autographed portraits of Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood, and since I had no other actual wallet-sized pictures to take their place, I just left them there.

There is also a picture of a large family gathering that Ashley sent despite fretting over the fact that no matter how many time she rephotographed it, the result looked blurry. It still looks blurry, but not because of anything she did. I believe her grandmother Idanel may be the teenager seated on the grass in front of a group of relatives. That seems to be her older sister Inez crouching behind Idanel, and the couple standing directly behind the two girls are their parents Isaac and Nettie. What’s the occasion? It has to be a more solemn event than a mere family reunion, perhaps the funeral of Isaac’s father, Morgan Josiah Williams, at Kingman, Kansas, in early March 1941.

The group may have been carefully arranged, but otherwise this is a spur-of-the-moment snapshot taken with a cheap camera, or at least a camera with a simple lens plagued by spherical aberration, which led to fuzziness at the edges. If only our ancestors possessed the sort of hardware we do, they could have taken as many razor-sharp pictures of each other as we take of our adorable cats. But then they probably wouldn’t seem so precious as the few faded and fuzzy pictures we have to treasure.