I was hoping that the Indian depredation claim files which Phil Thornton located at the National Archives would clear up a few niggling mysteries. For instance, did Ernest and Mary Ackerly and Walter Jackson, taking flight after an Indian attack on the afternoon of May 28, 1869, make their way by moonlight to the Lovewell cabin as Jewell County history insists, or did they find refuge with the Fraziers, as some witnesses remembered? Where was Thomas Lovewell during all of this? Did he head to Clifton to check on his family after his standoff with Dog Soldiers on the 27th, or was he one of the armed men guarding the Lovewell farm when Charles Murdock and his companions from Scandia stopped by the next afternoon?

None of these pesky details is much clearer today. However, quite expectedly, Phil uncovered evidence in the files that bolsters one of my assumptions about White Rock. Trouble with a capital “T” must have been simmering there for quite some time.

The files are sprinkled with interesting details, such as the fact that after the 1867 White Rock Massacre, Thomas Lovewell ran into Samuel Fisher on the road between White Rock and Clifton and assured Fisher that his family had been moved out of danger. It’s generally known that Samuel Fisher lost stock to Indian raiders and had to abandon his wheat crop, but thanks to Lovewell’s testimony we learn that there were “two 3 yr old colts worth $125 each that the mare was old and scarcely worth $30 and the other horses were a fine span of bay mares fully worth $325. That said wheat would run 30 bus to the acre and worth in the field unharvested $1.25 per bushel.”

It’s possible to put too much stock in those Indian depredation case files. By the time some of the affidavits were taken, twenty years had passed, memories must have developed tangles, and injured parties clearly had compared notes. Settlers often admitted that they did not know one Indian tribe from another, but that didn’t stop them from naming one. If they put the blame for their losses on Sioux warriors, it was only because William “Buckskin" Harrington had told everyone he recognized the Sioux language being spoken by his tormentors, and had identified an arrow pulled from Reuben Winklepleck’s body as having Sioux markings. Harrington had lived among the Sioux and knew their language and their handiwork. If settlers instead named the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho as the culprits, it was because Thomas Lovewell had said those three tribes were pillaging in concert during the late 1860’s. He had been an Army scout and must have known what he was talking about.

Refugees from Excelsior uniformly referred to the Lovewell farm as “Lovel’s.” The Excelsior compound was described by every witness as lying eighteen miles from the Lovewell and Frazier cabins. All sources agreed that William Frazier’s wagon had toted the Ackerlys and Jackson eight miles from the Excelsior camp to a clearing in the middle of nowhere when the Indians attacked. Perhaps it was equipped with an odometer, but did the Frazier brothers check the mileage as they frantically unhitched their team and prepared to gallop away with scores of Indians in hot pursuit? Everyone had his story straight. Or, at least most of them spoke in perfect unison except for that one fly in the ointment, Thomas Lovewell.

Allen Woodruff lost his team on Sunday the 23rd of May 1869, the same day young Thomas Voarness was killed by Indian intruders at the Dahl brothers’ cabin. He wanted to be compensated for the loss of his two horses and for a steer that disappeared about the same time. There were other items taken, but Woodruff felt that this was most likely the work of “white Indians.” “The worst of them were the scouts and members of the militia sent into the country to protect the settlers and then robbed them of what the Indians failed to take.”

“Said horses were captured by said Indians," Lovewell agreed when he was deposed in 1890, but “said steer was lost by said Woodruff while being driven, with a number of others, to a place of safety after the capture of said horses.” Eight years later, Allen Woodruff’s attorney tried to make Lovewell’s statement sound ambiguous, as if he may have meant to imply that the Indians had been driving the cattle. When asked to square this apparent contradiction from his star witness Woodruff replied, “I was there and Lovewell was not. He was over on the Republican River.” That much was true. Thomas Lovewell was leading his White Rock Rangers on a detail to bury four hunters from Rose Creek, Nebraska, who had been attacked by a large war party on the 20th or 21st.

In general, settlers who gave depositions vouched for one another’s reputation for truthfulness. All agreed that Mr. Lovewell was a man whose statements should be believed, although Mr. Lovewell did not always return the compliment. Two other witnesses to Woodruff’s loss were J. F. Fisher and Charles Hogan. J. F. should not be confused with Samuel Fisher’s son James T. Fisher, who died in 1871 and whose own farm lay near his father’s. There was an apparently unrelated J. F. Fisher who filed claims for $900 worth of stock to Cheyennes in 1867 and 1869. Hogan was a Swedish immigrant who had shared a log cabin with Peter Tanner on the opposite side of the creek from Paul and Martin Dahl and their nephew Thomas Voarness. Thomas Lovewell claimed familiarily with both Fisher and Hogan.

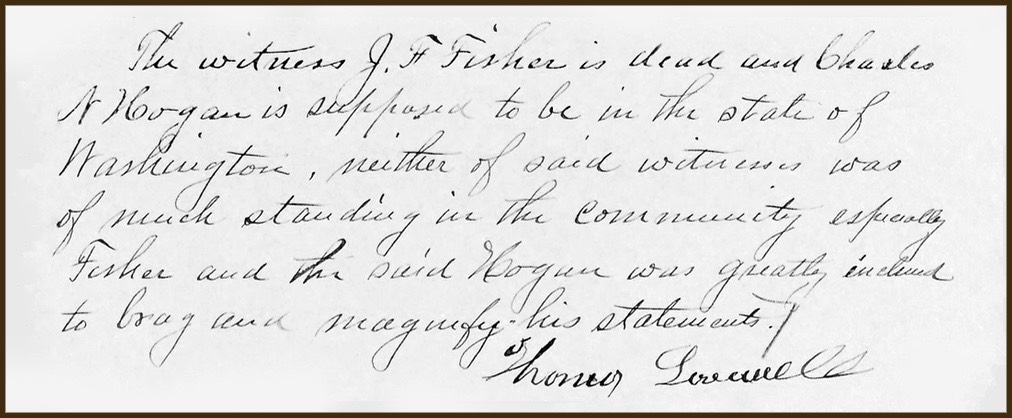

“The witness J. F. Fisher is dead,” Lovewell declared, "and Charles N. Hogan is supposed to be in the state of Washington. Neither of said witnesses was of much standing in the community especially Fisher and the said Hogan was greatly inclined to brag and magnify his statements.”

With one affidavit Thomas Lovewell had impugned three of his former neighbors, suggesting that Woodruff was demanding payment for a steer that wandered off on its own, and that anything Fisher and Hogan had to say about it was worthless. It’s further evidence that the relationship between Thomas Lovewell and the community around White Rock began to develop some cracks in the early going. His township’s stubborn refusal to fork over final payment for a bridge he built in 1878 was the most obvious sign, coming only two years after Lovewell filed the plat of the town. Lovewell's hints about moving to Oregon in 1886 probably indicate that he was finally fed up with the neighborhood. Changing his mind a year later and preparing to lay out a townsite four miles west of White Rock almost seems an act of vengeance. His decision to build the village of Lovewell would drive the final nail into White Rock’s coffin.

Several years ago, when I still believed in the myth of the early death of Thomas Lovewell’s first wife Nancy, I wasted weeks poring over records looking for some calamity that would explain the breakup of the family. Genealogist Mary Penner, with what seemed Yoda-like wisdom at the time, but was really just her usual clear-thinking, suggested, “Maybe they just didn’t like each other.”

There may have been a case of that with White Rock, too.