Stofer descendants haven’t just shared dozens of pictures pertaining to Lovewell family history. They’ve very nearly provided an illustrated guide to the first hundred years of photography.

In the previous blog post I mentioned Kodak’s postcard camera. This was a fairly expensive folding camera which took postcard-sized pictures that could be addressed on the back and sent anywhere in the country for a penny each as soon as they arrived from the lab. It must have seemed like an ingenious idea in 1903, perhaps not on a par with Edwin Land’s stunning development of instant photography a mere forty years later, but still innovative and useful. It led to a service that would print any negative on as many postcards as the customer wanted. This was surely what Fred Poole did with the photo of a washout on the Santa Fe Railroad in 1911 near Lovewell, before mailing out copies to a few cousins.

Fred's postcard is remarkable on two other counts that I didn’t mention last time. First, since Fred penned the date when the picture was taken on the bottom of the photo, we know that while the process was fairly simple, it still took some time. In this case about a month elapsed between the moment when the picture was snapped and the finished postcard was slipped into a mailbox. Part of that time must have been spent waiting for another photo-op. Back then, only a newspaper photographer would have pictures developed one at a time. Thrifty hobbyists and family photographers had to wait until an entire roll of film was used up before shipping it off for processing.

More importantly, we just don’t keep bundles of correspondence exchanged between family members, unless one of the relatives was famous, and his autograph could one day be worth something on eBay. We have that one from Fred only because there’s a photograph on the flip side of the message. While people tend to chuck out old letters, they'll stick old photographs in albums.

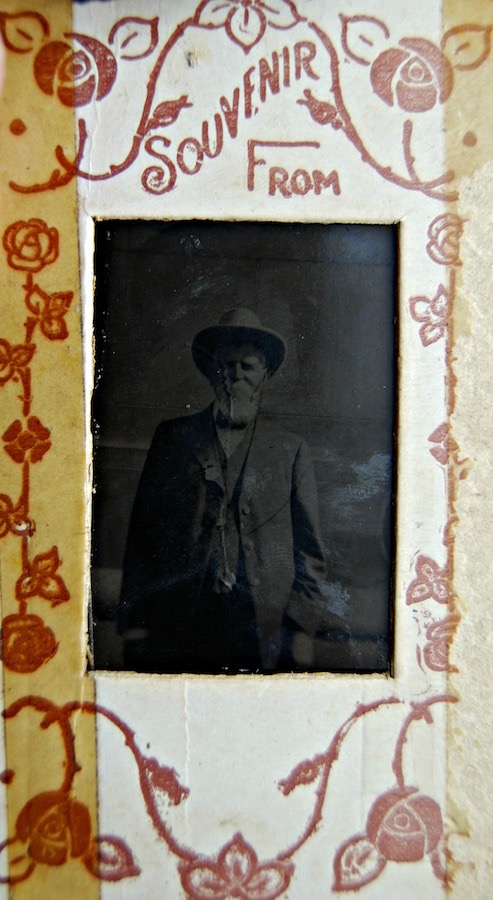

One of the photos Ashley Gresham sent recently struck me at first as an incompetently-made portrait, but it turns out to be one of the most interesting of the bunch. I felt sure this was another picture of Mary (Lovewell) Stofer’s father-in-law Jacob G. Stofer in his later years. The style of his beard, the creases around the mouth and the slope of his eyebrows (reminiscent of Mary’s husband Ben squinting at the sun), all suggest that it’s him.

But there’s also definitely something wrong with this picture. The buttons are on the wrong side of the gentleman’s coat, meaning that this has to be a form of tintype, a photographic process that results in a mirror image of the subject, and a process that was surely passé by the time Jake Stofer’s beard turned white. For a moment I wondered if the man in the photo might instead be Jake’s father William Stouffer, who refused to change the spelling of his last name to match his son’s. Then I realized that it had to be Jacob G. Stofer after all.

The opaque, murky likeness is not a professional portrait. It’s the sort of haphazard job we might expect from an overworked and minimally-talented cameraman operating a photo kiosk on a busy street corner or at a county fair. It all suddenly made sense. Even after tintypes were shoved to the sidelines by improvements in photographic chemistry, it thrived among hucksters who were in a rush to serve a clientele that wasn’t all that picky. Because there was no negative in tintype photography, there was no need for the extra step of creating a positive image on photographic paper. The man in the kiosk could just take the picture, dunk the slender photographic plate in some chemicals, sandwich it between two protective pieces of cardboard and hand it to the customer. It was no Polaroid, but it was a comparatively speedy operation.

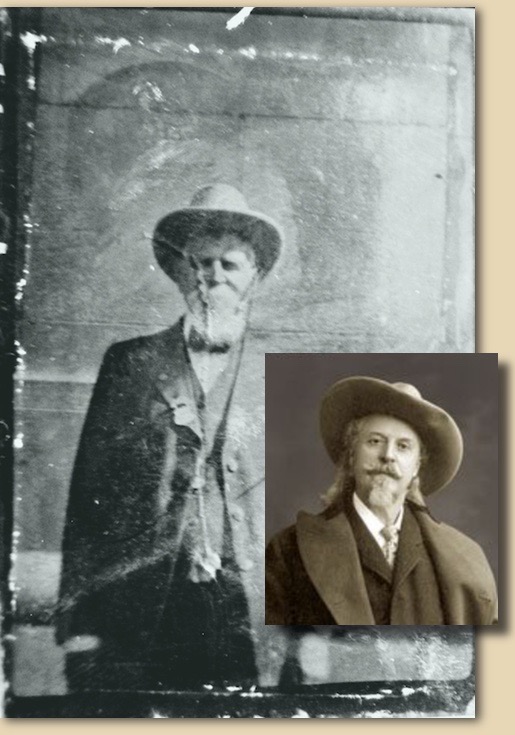

While we might surmise that most people went to fairs in those days, we know for a fact that Jake Stofer went to a really big one. According to the September 1, 1893 edition of the Scandia Journal, Jake and Zona White* stepped aboard a train bound for the World's Columbian Exposition, sometimes known as the Chicago World’s Fair. I was afraid I might be seeing things that weren’t there, when the faint image on a poster behind Mr. Stofer began to resemble the head of a man wearing a wide-brimmed cowboy hat. Then I began to push my imagination further, wondering if the subject of the cheaply-made photograph wasn’t at a fair at all, but a popular attraction just up the street from the Columbian Exposition, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.”

William Cody had been snubbed by the expo’s planners, who wanted their affair to be a lofty celebration of industrial progress. So, the wily showman rented an area between the train station and the official exhibits, put on a show that was the hit of the whole shebang and kept all the profits he raked in. That would explain why there is no World's Columbian Exposition logo on the vendor’s souvenir. Either that, or the sticker fell off. Or else, that’s not where the tintype was made, which it isn't.

I’m afraid the souvenir was produced elsewhere, long after the Columbian Exposition closed its doors, even though I believe most of my guesswork is fairly close to the mark. The picture of Jake Stofer was almost certainly taken in Fairbury, Nebraska in July 1915.

Even though Jake Stofer and Zona White no doubt shared an excellent adventure in Chicago, and probably didn’t pass up a chance to see a very early incarnation of Buffalo Bill’s touring show in 1893, I don’t think the picture is a souvenir of that particular trip. Well, maybe sort of, but not really. For one thing, Jake Stofer would have been 49 years old in 1893, much too young to be sporting such a hoary set of whiskers. For another, if that is indeed a painting of William Cody behind him (and I think it is), the tilt of Cody's hat looks remarkably similar to one in a photo (inset to the right of Stofer) apparently used as a model in preparing advertising art for the Sells-Floto Circus, which, to Cody’s infinite regret, teamed up with “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” during the Western show’s ride into the sunset in 1914 and 1915.

On its tour through the middle of the country in 1915, the Sells-Floto Circus set up its tents in Fairbury, Nebraska, a hop and a skip from Jake Stofer’s home in Scandia, Kansas. Twenty-two years after his trip to Chicago, Stofer may have decided to relive a fond memory, remembering to snag a memento this time. So, in a way, we may think of it as a souvenir of that earlier trip.

I’m afraid I’ve taken a long-winded route to arrive at this point, explaining why buttons on the wrong side of his coat and a white beard on his chin can only mean that Jake Stofer had a tintype taken by by a circus employee in front of an indistinct poster of William Cody at Fairbury in 1915. That’s the explanation that makes the most sense, and the only one I can think of that fits all known and apparent facts.

Hardly any alternative facts were used in reaching this conclusion.

* “Zona” was short for “Arizona," the name of Jacob Stofer’s son-in-law

Tintype and photographic copy provided by Ashley Gresham