I like to make these installments brief, for both your sake and mine, even though there's more that's worth telling about Dr. Kilmer and his brother Jonas and their families, residents of Binghamton, New York, who were swimming in riches provided by the brisk sales of Swamp-Root Kidney, Liver and Bladder Tonic.

When the Binghamton Herald printed details about marketing genius Willis Sharpe Kilmer's public tantrums and legal entanglements, the millionaire retaliated by withdrawing his company’s Swamp-Root advertising from the pages of the Herald for a few months. After the same paper printed a wisecrack about patent medicines, not only did Kilmer turn off the advertising spigot, so did Lydia Pinkham, the manufacturer of a popular tonic for female problems. If a newspaper was going to wage war against the "snake oil” business, then that business would punch back, aiming for the tender spot where papers would feel it most dearly - advertising dollars.

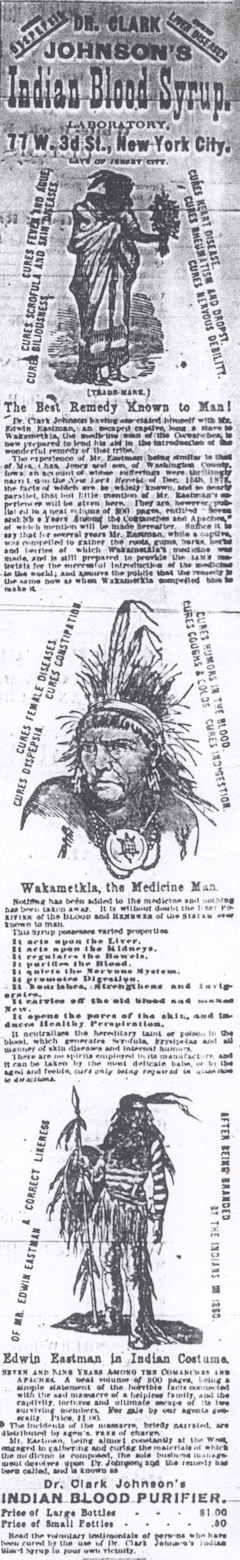

Dr. Kilmer cooked up his first batch of Swamp Root in 1878, early enough that he could have advertised his miracle-in-a-bottle in Thomas Lovewell’s hometown paper, the White Rock Independent, which was published during the second half of 1879. With Swamp Root fresh on my mind I took another look at my photocopy of a page from the Independent, paying close attention to the ads this time. The name “Swamp Root” had sounded distasteful until I read about Dr. Clark Johnson’s Indian Blood Syrup.

What I had never noticed before was how this full column of the Independent was not merely devoted to touting the wonders of a potion that cured everything from heart disease to coughs and colds, but took pains to give the medicine a plausible backstory.

Dr. Clark Johnson having associated himself with Mr. Edwin Eastman, an escaped captive, long a slave to Wakametkla, the medicine man of the Comanches is now prepared to lend his aid in the introduction of the wonderful remedy of that tribe.

Suffice it to say that for several years Mr. Eastman, while a captive, was compelled to gather the roots, gums, barks, herbs and berries of which Wakametkla’s medicine was made, and is still prepared to provide the same materials for the successful introduction of the medicine to the world; and assures the public that the remedy is the same now as when Wakametkla compelled him to make it.

The advertisement further points out that the tale of Edwin Eastman’s captivity is fully recounted “in a neat volume of 300 pages.” Never mentioned is the fact that the memoir was published in 1873 by Dr. Clark Johnson, presumably the same Dr. Johnson whose name appears on every bottle of the miracle cure. The very firm offering large bottles of Indian Blood Purifier for a dollar each, was also willing to send along a copy of Eastman’s book for another dollar, or an outline for free.

Hoping to bolster the book’s credibility, the ad points out that Eastman’s experience was “similar to that of Mrs. Chas. Jones and son, of Washington County, Iowa, an account of whose sufferings were thrillingly narrated in the New York Herald of Dec. 15th, 1878…” In other words, the events in the Eastman book should be accepted at face value, because they're similar to stories reported by actual captives and printed in a reputable newspaper.

While the supposed memoir of Edwin Eastman appears in a few modern lists along with undisputed accounts of Indian captivity, some readers versed in frontier lore have found Eastman’s details of life among the Comanches highly suspect. Still others speculate that both Edwin Eastman and Dr. Clark Johnson were fictions created by a nameless press agent looking for a gimmick that would help his firm peddle bottles of sugar-water to innocent sufferers.

Neither Swamp Root nor Indian Blood Syrup had any known medicinal value, except, perhaps, for a temporary placebo effect. Dr. Kilmer’s potion also provided a brief palliative buzz, since it was 10% alcohol. Dr. Johnson, whoever he was, advertised his as alcohol-free, which allowed it to double as a pediatric tonic.

Their genuine contribution to frontier life may have been the dollars they added to the till of small-town newspapers, such as the White Rock Independent. The income provided by snake oil may have been meager, but it was something country editors could count on, so long as Willis Kilmer’s nose wasn’t out of joint about something he read in the paper.