Once in a great while I’ll write about a new movie, especially if it connects with Thomas Lovewell’s timeline, or the family’s story. This is one of those with a couple of connections to Lovewell history, and anyone who recalls my entry from last year, “Lovewell Goes Ape,” will already know one of them. For much of 1914, readers of the Lovewell Index were immersed in the adventures of the orphaned son of an English Lord who was adopted by apes. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ stories “Tarzan of the Apes” and “The Return of Tarzan” were serialized in newspapers across the United States, becoming the second and third titles to pad out pages of the Index. Burroughs may have struck a chord with pioneers and their descendants in Jewell and Republic counties by holding out hope that there were still new frontiers waiting to be explored - even if they did lie at the earth’s core or on the far-off heavenly bodies of Mars and Venus. However, when Burroughs set one of his imaginative frontier tales right here on the surface of Planet Earth, in the interior of darkest Africa, he struck gold.

A producer - it may have been Sy Weintraub, who guided the series through the late 1950’s and early ’60’s - announced that he had found the key to making a good Tarzan adventure. It was important that the plot of the movie should not be centered on the ape-man per se, who was to be treated as an extra character. The film needed a solid story peopled with interesting protagonists caught up in diabolical machinations, and then at a key moment, they all meet up with Tarzan, who will save the day.

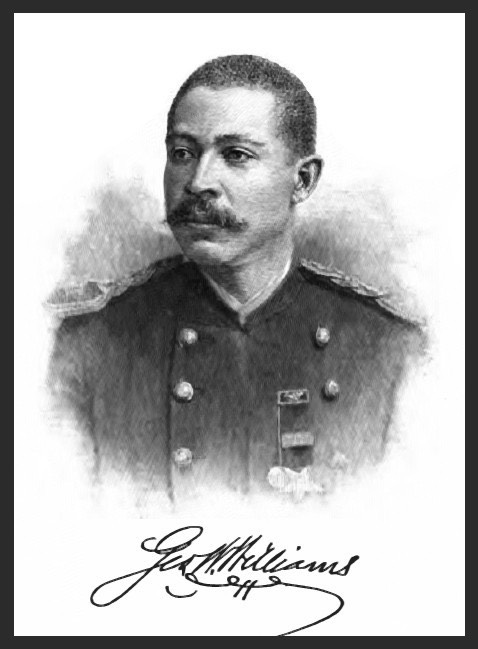

The creators of the new Tarzan movie, “The Legend of Tarzan,” apparently paid heed to Sol Weintraub, because their film is crammed full of story, some of it drawn from history books and classic literature. Christoph Waltz, a brilliant specialist in playing articulate, soft-spoken villains, portrays Léon Rom, a real-life Belgian army captain and colonial administrator who, some critics believe, may have been the model for Joseph Conrad’s mad Mr. Kurtz the ivory trader in “Heart of Darkness.” Another real person enmeshed in the drama, George Washington Williams, is played in the film by a fine and unusually restrained Samuel L. Jackson. Williams was an African-American Civil War veteran, lawyer, writer, and adventurer who, after a fact-finding mission to the Congo Free State, wrote an open letter to King Léopold of Belgium, castigating the king and other colonial powers for their brutal treatment of the native population.

In the film, it is Tarzan, in his role as the 5th Earl of Greystoke, who is invited to tour the Congo Free State. Samuel Jackson’s George Washington Williams convinces Tarzan to accept the invitation and allow him tag along to see if his worst fears about the evils of colonialism are borne out. It makes for a sobering history lesson, a poignant Tarzan/Jane love story, and a corker of an adventure yarn. The film also provides an amusing twist on “Heart of Darkness” and, by extension, Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” As they steam upriver, ever deeper into the forbidding miasma of the jungle, Joseph Conrad's Kurtz and Marlow shed the veneer of civilization to confront the savage beast within themselves. That’s a terrible fate, unless you’re Tarzan, who is simply a local boy headed home, returning to the wellspring of his strength.

I mentioned that there is another Lovewell connection to the film, or perhaps I should say a near-connection. After the Civil War and a stint in the Mexican Army, the real George Washington Williams joined the 10th Cavalry to fight in the Plains Indian War. Signing up in the spring of 1867, Williams was still only about 18 years old when he traveled to Fort Riley, where regimental commander Col. Benjamin Grierson recognized the young man’s talent and experience, and made him a drill sergeant. It was men from the 10th at Fort Riley whom Thomas Lovewell guided around the plains of Kansas that summer, although Williams arrived at the fort too late to make the march to Camp Hoffman on White Rock Creek. He was deployed to Indian Territory where his military career would be cut short by an Indian arrow, according to the story Williams told, although a biographer reports that he was hospitalized with a non-combat related gunshot wound.

His life would also be cut short by his excursion to Africa. Williams never returned to America, dying in England of tuberculosis and pleurisy in 1891, at the age of 41. It may have been a brief life, but he had packed a lot into it. As if knowing that time was short, he seldom did any one thing for very long. He attended Howard University for a while, served a single term in the Ohio State Legislature, studied law, and was appointed Consul General to Haiti, although he never served. He founded a monthly Boston newspaper called The Commoner, but published only eight issues. After graduating from Newton Seminary he became a Baptist minister, serving as pastor at several churches, among them the historic Twelfth Baptist Church in Boston.

Today he is remembered as the author of two ground-breaking studies, The History of the Negro Race in America and A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion. Of course all of his accomplishments are now eclipsed, for some, by being portrayed on the screen by Samuel L. Jackson. That, and knowing Tarzan personally.