New writings by Lovewell authors have recently surfaced on Archive.org. Well, they’re not new writings, exactly, but some of them may be new to us.

I’ve been trying to get my hands on Rev. Lyman Lovewell’s “A Sermon on American Slavery - Preached in New Hudson, Mich., June 18, 1854” ever since I first heard of it. Lyman was probably the driving force behind the arrival of Thomas and Nancy Lovewell and the entire Vinson Davis clan in Kansas Territory in the spring of 1856, and I’ve been curious to know what he had to say on the subject. There are a few bound copies of the sermon crumbling in public libraries located quite some distance from my house, but the only one readily available was from an on-demand copying service in Australia. Then, as I do from time to time, I checked yesterday at my favorite online resource for quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore, Archive.org, and there was Lovewell’s “Sermon on American Slavery." I hope I’m not spoiling the fun for anyone by revealing that he was dead-set against it.

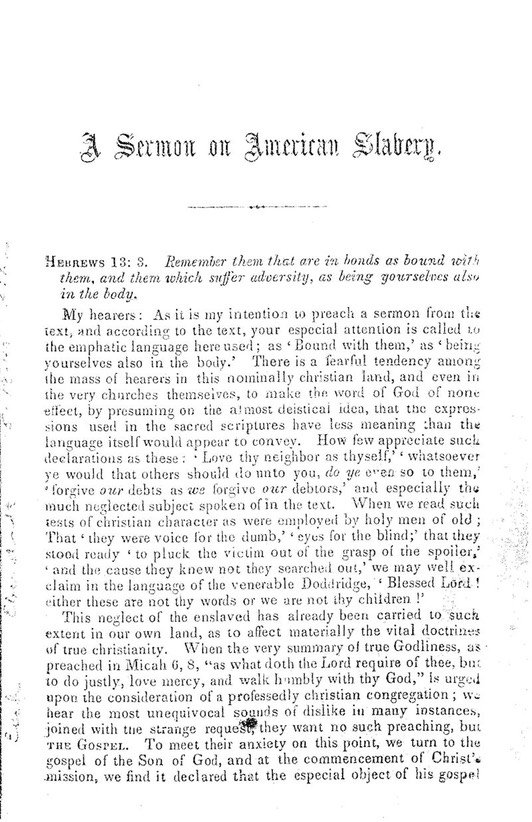

Mr. Lovewell, who was a Presbyterian minister, made some of the arguments we would expect against America's peculiar institution, those culled from Sacred Scriptures, such as the one he cites as his text for the occasion, Hebrews 13: 3. Remember them that are in bonds as bound with them, and them which suffer adversity, as being yourselves in the body.

A few things struck me at the outset. The title page, pictured here, is the one with the fewest number of words on it, and there are seventeen pages in all. I rattled off an average-looking page aloud and took three minutes doing it. Allowing for dramatic emphasis and the occasional “Amen,” the sermon would have taken well over an hour to deliver, in addition to whatever hymns, offerings, and prayers constituted a regular Presbyterian service in 1854. There must have been some grumbling tummies in the Rev. Lovewell's congregation on the 18th of June.

Besides using scriptural exhortations, Lyman Lovewell also attacked the evils of slavery with appeals to pride of country, and, most surprisingly, with statistics. He may have been a man of the cloth who believed in the truth of the Word, but Lyman also believed that numbers don't lie. He used details from the 1850 census to compile contrasting figures, balancing the number of inhabitants of slave states who could not read or write, against the number of illiterate inhabitants in free states.

"In the fertile State of Georgia, 41,260; in cold, hardy Maine, 2,134; Virginia ‘the mother of Presidents,’ 87,383; Massachusetts, ‘the land of laborers,’ 1,861.”

As I did a cursory glance over the pages, I thought there had to be something wrong with Lyman’s calculations. Surely the slave populations of Georgia and Virginia had to be much higher than that. Then I realized that I had overlooked an important and obvious point. He was counting only the number of illiterate free inhabitants over the age of twenty in all states. Simply living in a State that outlawed literacy among a slave population, seemed to devalue literacy among all its inhabitants.

Another feature of the slave system may be seen in the fact that it takes some eight prominent slave states to form a population of free people equal to the single state of New York, and view the difference in educational interests of these States, of the free native population over twenty years of age. The state of New York has 30,630 who cannot read and write, in some over three millions of people, while the States of Virginia, North and South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas, containing in all about the same free population, will furnish 270,411 of this degraded class.

Slavery was not only un-Christian and immoral, it bred ignorance. Open the door for slavery, Lyman Lovewell argued, and literacy goes out the window. Not only did slave states have a higher incidence of residents who could not read or write, the number seemed to increase at an alarming rate. He quoted from a Richmond paper which reported that “In 1840, the number of unlettered in Virginia amounted to 60,000. In 1850 it exceeded 80,000. At this rate it will not require many centuries to extinguish all knowledge of letters in the State.”

Unfortunately, Lyman did not live long enough to see the end of slavery instead of the end of letters in the State of Virginia. He died of typhoid fever at the age of forty-nine in 1862.

Death often seemed to arrive ahead of schedule in the 1800’s, as Prof. J. T. Lovewell once pointed out. The professor was a cousin of Thomas Lovewell and the father of Marguerite and Carolyn Lovewell, who've been featured on these pages lately. Many of Jospeh Taplin Lovewell's science writings are also now available on Archive.org, including one of his briefest, “The Longevity of Yale Graduates, as Shown by the Publication of Living Graduates of Yale University, 1912.” The professor seemed to have a vested interest in the subject, since both he and his brother John were Yale grads.

Given the statistics that were being compiled at Yale, the professor did what any self-respecting man of science would do - he created a chart, plotted a graph and wrote a short piece on the subject. Nothing in it was especially earth-shattering news.

“The death rate is low for a few years succeeding graduation, as might be expected of young men in the prime of life. As the years go on the curve drops down and shows that about 50 per cent survive forty to forty-five years after graduation. It takes about twenty years to cut down the first 10 per cent of a class. Ten percent more will be gone in about fourteen years more. An equal period will now remove as many as 20 per cent, while, as said above, 50 per cent will be dead in another ten years. As we approach the limit of seventy-five years the percentage of loss grows less, for at this period there are generally a few cases of extreme longevity, and these withered leaves drop off more slowly."

By the early 20th century about half of Yale graduates, who must have been somewhat better-off than average, were reaching the advanced age of 68. When the professor, a member of the class of ’57, published his paper on the longevity of Yale men, fewer than 25% of his own classmates were still living. He was one of those withered leaves reluctant to drop off, refusing to take his place in the necrology column of the Yale Alumni Weekly until 1918.