“The Life of St. Cecilia” a detailed examination of a pair of Middle English manuscripts conducted by Bertha Ellen Lovewell, Ph.D., is a work dedicated to her father, Prof. J. T. Lovewell, who was not only a scientist but a Latin scholar. However, the book may also have been partly intended as a tribute to Bertha's stepmother, Caroline Forbes Barnes Lovewell. St. Cecilia is the patron saint of musicians, and while no one ever publicly accused Prof. Lovewell of being able to carry a tune, the second Mrs. Lovewell not only founded the music department at Washburn College but schooled her own daughters in the musical arts.

Born in 1867, Bertha graduated from Washburn with a Bachelor of Law degree in 1889, entering Yale Graduate School the moment it was opened to women in 1892. Her treatise on the beloved Roman saint was published in 1898, the year Bertha’s half-sisters and future musicians Marguerite and Carolyn Lovewell turned twelve and eight years old.

According to the legend of Cecilia, a high-born Roman woman by that name was martyred for her Christian faith around 200 A.D. Condemned to death after refusing to sacrifice to the traditional Roman gods, she survived a plot to fatally scald or smother her in her upstairs vapor bath, emerging purer than ever and with a healthy glow. The task of getting rid of her was handed to a professional executioner, but there was evidently a three-strokes-and-you’re-out policy in those days. On his third swing, the man wielding the blade managed to inflict a mortal wound, though one that gave Cecilia three days of supine prayer which she also used to put her affairs in order, give away all her worldly goods to the poor, and offer her palatial home as a place of worship.

When her tomb was discovered six hundred years later, her incorruptible body lay in a cyprus coffin, arranged in the same pose of tranquil prayer she had assumed as she lay dying on the floor. Anyway, that’s the story we’re given. In the preface to her translation of texts involving the legend of Cecilia, Bertha Lovewell wrote:

Until, as Dr. Horstmann has observed, the combined intelligence of generations yet to come has been applied to the problem, many of the most vital questions relating to English Legendary must remain unsolved. Perhaps the best service which can now be rendered, is to continue to present … accurate reprints of existing versions, together with textual studies of the kinds familiar to scholarship.

I guessed that Bertha’s preface might be a variation of director John Ford’s advice to "print the legend,” but a passage later in the work indicates that she was completely serious about holding the legend’s feet to the fire with rigorous textual analysis.

There can be little doubt … that the Acts of St. Cecilia rest upon a basis of fact. It is also doubtless the case that pious exaggeration and misapprehension, together with errors fixed by centuries of historical inaccuracy and insufficiency, have together conspired to produce a medieval account which, as it stands, is antagonistic to its own veracity.

She then proceeds to point out parts that might be true versus what is obviously false, by connecting elements of the legend with archeological evidence and with the documented lives of historical persons associated with the tales of early martyrs. I can understand Bertha’s impatience with the old stories about Cecilia. I've had to wade through my own share of "pious exaggerations" while studying family history. I also quite like her phrase “antagonistic to its own veracity,” and plan to borrow it in the near future. There are a few politicians right here in Kansas who’ve become antagonistic to their own veracity - but I digress.

Bertha Lovewell’s name can often be found listed in the membership rolls of her local Browning Society. In case you’re wondering if she preferred the Browning 1890 pump action that William Frank Lovewell may have used to shoot out the lights of Santa Fe No. 7 as it roared past Lovewell toward Webber - please take this stuff seriously. Bertha was an enthusiastic fan of poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and her passion sometimes gave her the opportunity to perform alongside her half-sister Marguerite, Bertha lecturing the audience about the Brownings, with Marguerite performing a song-cycle based on their works. It seemed almost inevitable that Bertha Ellen Lovewell would marry a man from the northeast named Dickinson. Marguerite Lovewell would marry Harry Kingsley Grigg at the home of George and Bertha Lovewell Dickinson, or at least in their West Coast hometown of Pasadena, California.

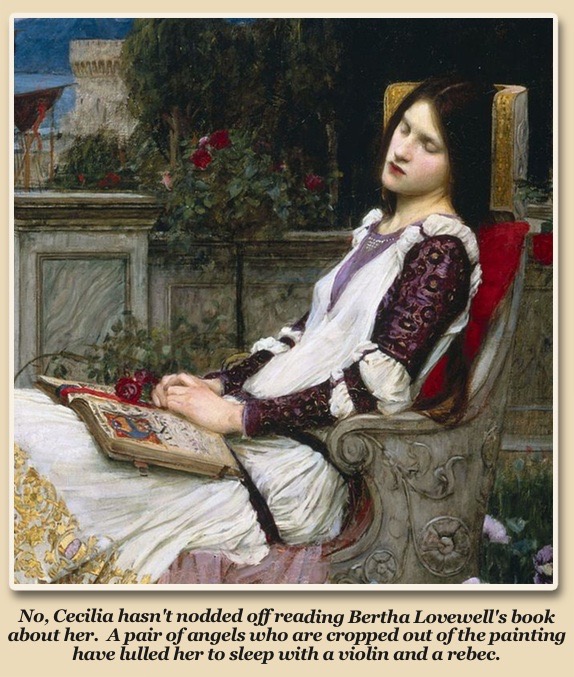

Today, outside of the Catholic faith, we most commonly encounter Cecilia in art and music, the Paul Simon song quoted in the title of this piece, for example, along with scads of paintings and sculptures. I googled images of her and let my web browser create a mosaic. The picture shown here represents the top third of the resulting page. There is even a well-populated subset category of oil paintings of famous ladies masquerading as the saint. She remains the subject of heartfelt veneration as well as desperate pleas from struggling songwriters to stop spending her afternoons with someone else, and to please come home.